South Asian states have experienced refugee movements since independence from the British colonial rule and yet once again in 1971 when East Pakistan was split from West Pakistan. The territory of India as it is today has been at the forefront of this influx along with two other nations in the region – Pakistan and Bangladesh while Afghanistan has been a state that has sent out its citizens as refugees all along due to the state of prolonged internal conflicts, and in its immediate neighborhood.

According to the United Nations, the projected number of refugees is estimated to be around 2.5 million in South Asia, with India alone hosting around 2,00,000 (number registered with UNHCR). Unofficially, India is said to have nearly 437,000 refugees. It is not only the regional atmosphere but also the volatility of the countries in neighboring regions – Syria, Iraq, Tibet and Myanmar that have led to an exodus of populations into South Asia. Apart from wars and persecution, economic deprivation and climate change are driving people out of their home countries. India, sharing borders with all of the South Asian countries where Maldives being contiguous in the Indian Ocean Region, has inevitably been the first or second destination for refugees fleeing their homes. However, India has failed to adopt a legal framework to confer refugee status to people who have fled home countries for a well-founded fear of persecution, discrimination or deprivation of any kind thus blurring the lines between migrants who have entered illegally and refugees.

Recently, India passed the Citizenship Amendment Act that seeks to grant citizenship to Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, Jains, Parsis and Sikhs who entered India before the 31st of December 2015 from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. The Act has an arbitrary cut-off date, omits the mention of Muslims, does not convincingly explain the rationale behind grouping the three countries, thus any argument of replacing the ad hoc refugee policy would only stand frail. This article, with this premise at the crux will attempt to examine why India has to work towards formulating a holistic refugee policy framework followed by a law and how there is a need for one to ensure the domestic population does not turn hostile to refugees.

Understanding Refugees in India

India has allowed for the entry of refugees under the Foreigners Act, 1946; The Foreigners Order, 1948; Registration of Foreigners Act, 1939; and The Passport Act (Entry into India), 1920; The Passport Act, 1967. Refugee populations from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Eritrea, Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Tibet among many other countries have crossed borders to enter India due to sectarian conflicts, political instability and even economic and climate change.

South Asia is one of the most disaster-prone regions of the earth and has in recent years witnessed droughts, heatwaves, floods and rise in sea levels threatening both human lives and livelihoods for indefinite periods. Around 46 million people are estimated to have fled their homes in South Asia due to natural disasters between 2008 and 2013 despite a lack of precise estimate in how many have solely migrated due to climate change other than seasonal migration. This thus creates an intersection between economic and climate-induced migration. An estimated 20 million have been migrating from Bangladesh to India every year due to environmental adversities.

However, it has only been the discourse on traditional security that has dominated the discussions outside of academia questioning the preparedness of India in managing the influx of refugees in the run-up to global and regional crises due to non-traditional securities such as environmental degradation and resulting ‘environment-economic’ splinter effects.

Diplomacy vis a vis domestic governance

While we are already witnessing how different sections of the society have not taken it well to religious narrative embedded in the Act, several other factors have also threaded themselves to the dismay of locals due to lack of concentrated effort to treat refugees. Refugees who fear deportation and brutal treatment under the law may disguise themselves as residents and thus in the long run contributing to the alarm and insecurity amongst the locals. This has been very evident in Assam that has for decades agitated over the growth in population in the state due to illegal migration from Bangladesh. It was more to do with struggle for resources, fears of demographic changes and losing control of governance, and less about religion. By resorting to naturalizing refugees and not resorting to repatriation agreements, India today maybe adding fire to the already burning fuel of ‘more mouths to feed and fewer resources’.

India’s ad hoc policy has given it a leeway to treat refugees based on the country of origin depending on the geopolitics of the day. Today by sealing this arbitrariness as a law India has threatened its own scope to rectify its position in the wake of contestations. It is uncertain even being a signatory to The New York Declaration of Refugees and Migrants 2016, the precursor to the Global Compact on Refugees can realize India’s image as a responsible power while denying Rohingyas and Sri Lankan Tamils the due recognition as refugees.

On the global stage, India’s treatment of refugees had until recently attracted a fair share of appreciation despite the lack of a national refugee law and notwithstanding the fact that the country is a non-signatory to the United Nations Refugee Convention nor the 1967 Protocol.

India may not have an official reason on why it has not signed the convention, but sufficient correlative studies show us India’s skepticism arising due to the Euro-centrism of the convention, a threat to sovereignty and a narrow definition of refugees that does not cover the economic, social, and political aspects. Apart from this, the episodes of 1971 influx of refugees and earlier in 1945 linger over India’s unpleasant memories.

Conclusion

No refugee policy or domestic law remains an internal concern especially in South Asia where not only are the territorial borders porous but so are the divisions between communities. Due to its relatively better availability of economic opportunity and being a secular state, Indian policymakers are challenged by protracted refugee situations.

Given the pressure on India’s resources from its huge and growing population, it does not have the capacity to host large refugee populations. India, therefore, has to evolve a 21st-century diplomatic mechanism with both the global community and the sending states to create opportunities for resettlement of refugees. With evolving geopolitics and rise of non-traditional security, it would be in India’s best interests to formulate multifaceted refugee policies bilaterally and multilaterally.

Jayashri Ramesh Sundaram holds a masters in IR from RSIS, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. She focuses on refugee issues and policy analysis. Views expressed are the author’s own.

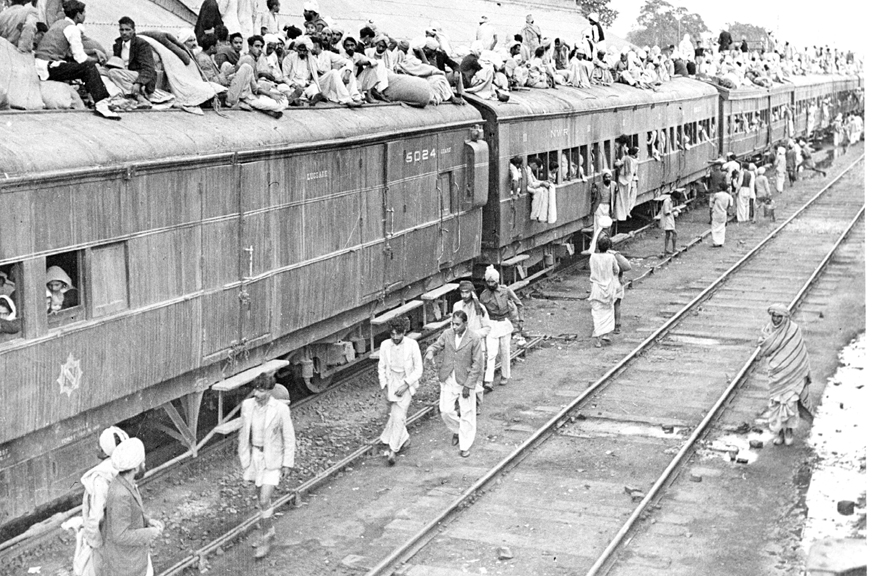

Image Credit: A Refugee special train during Partition. commons.wikipedia.org