The sculpted marvels which bejewel the ancient temples all across Tamil Nadu stand testimony to the magnificence of Sangam age (3rd century BC to 3rd century AD) and the prolific artistic innovations which are characteristic of that period. But that’s not all there is to it. Matching the artistic and cultural fervour, trade activities were also at an all-time high during the Sangam age. Evidentiating this claim, the Sangam literature chronicles details of all the fine merchandise which were produced in Ancient Tamilakam. Building up on their strengths, the Tamils ventured into lands far and wide, establishing trading associations in foreign countries, some of which till date retain imprints of their existence. Coupled with manifest cultural similarities, archaeological and inscriptional evidence add on to the credibility of Sangam literature by making a strong case for the existence of an extensive trade between Tamilakam and the rest of the Old World.

Sangam Literature: Valuable source of Information on Trade

Pattinappalai, one of the poems (301 lines in ‘Vanji’ meter and Asiriyapa/Akaval meter) in Pattuppāṭṭu which is a corpus of ten poems, talks in great detail about Kaveripoompattinam, the capital city of the Early Cholas.

Even though only half of what is claimed to have been created remains, the Sangam literature is too big a chunk to be thoroughly studied in a short time. There might still be parts of it that are waiting to be looked into. But of what has been discovered, the details pertinent to trade can predominantly be found in three major literary works, namely Pattuppāṭṭu, Silappatikaram and its sequel Manimekalai. Pattinappalai, one of the poems (301 lines in ‘Vanji’ meter and Asiriyapa/Akaval meter) in Pattuppāṭṭu which is a corpus of ten poems, talks in great detail about Kaveripoompattinam, the capital city of the Early Cholas. The port of Puhar / Kaveripoompattinam had ” an abundance of horses brought over the seas, sacks of black pepper brought overland in carts, gemstones and gold from the northern mountains, and sandalwood and eaglewood from the Western hills, pearls from the southern seas and coral from the eastern seas, grains from the regions of Ganga and Kaveri, food grains from Eelam (Sri Lanka) and products from Burma and other rare and great commodities.”

A description of the port warehouses of Kaveripoompattinam in Pattuppattu is revealing of the flourishing trade – “Like the monsoon season when clouds absorb ocean waters and come down as rains on mountains, limitless goods for export come from inland and imported goods arrive in ships. Fierce, powerful tax collectors are at the warehouses collecting taxes and stamping the Chola tiger symbols on goods that are to be exported.”

Silappatikaram and Manimekalai, on the other hand, talk about the cities of Madurai, Puhar and Kanchipuram, which served as major centres for cloth weaving, from whence fine quality fabrics were manufactured and exported through the Coromandel Coast. Silk, cotton and wool are some of the fabrics which are mentioned to have been exported from the coast. The epics also present a vivid description of the urban market scenes. The details paint the picture of a buzzing market where trade was carried out in a variety of supreme quality products, starting from agricultural products like black pepper, food grains, areca nuts, white sugar, eaglewood to luxury commodities like gold, pearls, gems, jewels, coral and silk, among other things. In fact, the urban markets are said to have had a separate street dedicated to food grains alone. So high was the demand for food grains that despite having close to eighteen indigenous varieties, grains also had to be imported from other countries in exchange for white salt. Likewise, the demand for aromatic products were too high to be met by home-gown eagle woods and sandalwoods, resulting in the import of the same from South East Asian countries, particularly from China and Indonesia.

Tamilakam: Maritime Trade hub-centre between the East and the West

Both literary and archaeological evidence have time and again reaffirmed one another; the merchants of Tamilakam had traded with the East and the West with equal flair. While there is a substantial amount foreign and native literature, and archaeological findings to assert the latter, there is relatively less evidence to support the former. And not only did Tamilakam engage in direct trade with the West, but because all products from Southeast Asia had to be sent through ports along the coast of South India, Tamilakam also acted as the hub-centre for the trade between the East and the West.

Commodities from Tamilakam had a great demand in Rome. Black pepper, cardamom, pearls and gemstones, especially Beryl which was mined from sites in Kodumanal, Padiyur and Vaniyampadi, were highly sought after in Rome.

With regard to the West, Tamil merchants have had a long-standing trade relationship with the Egyptians and the Romans. Beginning from the period when Alexandria was the centre of Mediterranean commerce, trade with the West extended well into the time when Rome assumed dominance and became the centre-stage of Mediterranean economy. Trade with Tamilakam was in fact a deciding factor in the question of dominance in sea trade. The Arabs held ground against the competing Romans by monopolizing the knowledge regarding direct sea route to India and information about the source markets in India. Nevertheless, eventually the Romans established direct trade links with India and Rome became the largest market ground for Indian products. Commodities from Tamilakam had a great demand in Rome. Black pepper, cardamom, pearls and gemstones, especially Beryl which was mined from sites in Kodumanal, Padiyur and Vaniyampadi, were highly sought after in Rome.

Picture: Interpretation map from ‘The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea”.

In the interpretations of a historical document called ‘The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, originally authored by a Greek Navigator in the 1st century, there is said to have been mentions of a marketplace called Poduk’e in the historical text . G.W.B. Hunting Ford, a historian, has postulated that this place might have been Arikamedu, a location two miles away from modern day Pondicherry. Hunting Ford also notes that Roman pottery have been excavated in Arikamedu and that these evidence point at the possibility that this region might have been a trading centre for Roman goods in the 1st century AD. Arikamedu, known as Poduk’e in the Greco-Roman world was a manufacturing hub of textiles particularly of Muslin clothes, fine terracotta objects, jewelleries from beads of precious and semi-precious stones, glass and gold. The city had an extensive glass bead manufacturing facilities and is considered as “mother of all bead centres” in the world. Most of their production were aimed for export.

Picture: Arikamedu – credit: Wikipedia

Arikamedu, known as Poduk’e in the Greco-Roman world was a manufacturing hub of textiles particularly of Muslin clothes, fine terracotta objects, jewelleries from beads of precious and semi-precious stones, glass and gold. The city had an extensive glass bead manufacturing facilities and is considered as “mother of all bead centres” in the world.

Descriptions of Puhar, Korkai, Muziris and Arikamedu in Sangam literature indicate extensive presence of Yavanas’ (foreigners) settlements in port cities on account of trade. Pattinapalai describes the port activities and the Chola customs revenue system in detail.

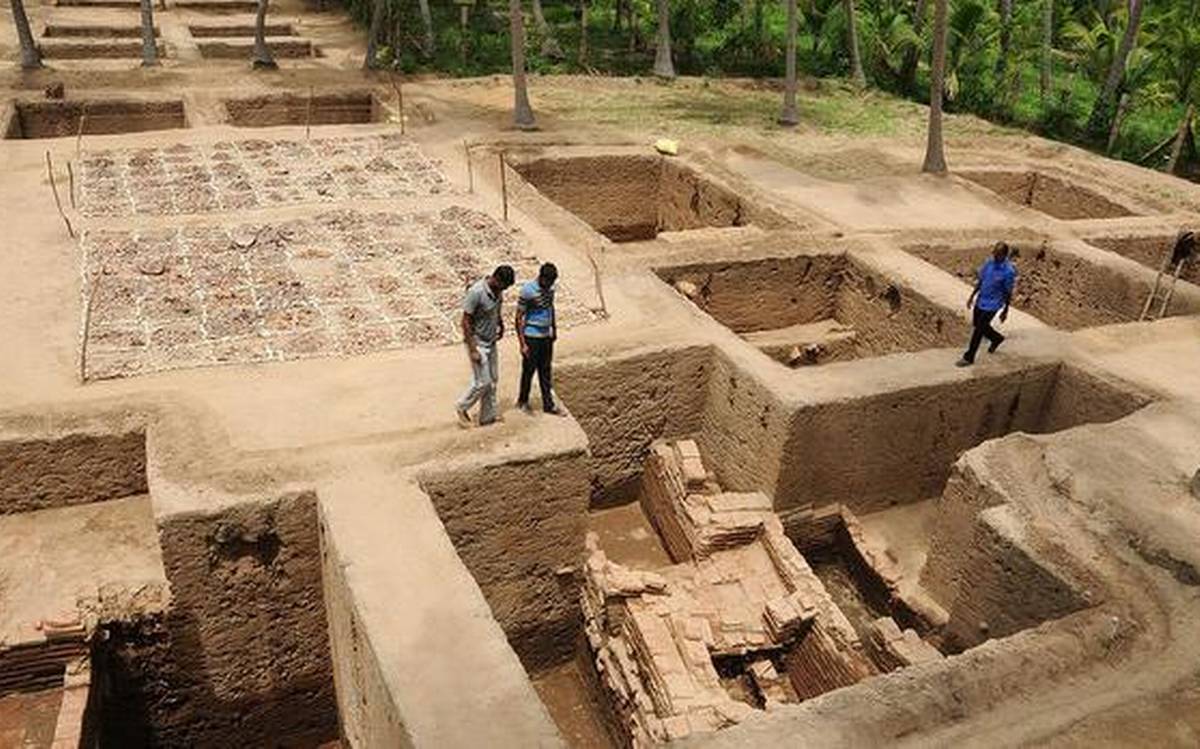

Keezhadi: Evidences of Industrial and Trade Centre

In addition to these, the Keezhadi excavation, conducted by the Archaeological Survey of India in 2016, has unearthed around 13000 antiquities like shells, glass beads, rusted old coins, weapons, pottery of various kinds and iron tools, belonging to the Sangam age. Among the fine quality red and black ware bowls excavated in the region, are the Roman roulette wares which evidentiate the existence of trade links between the Tamils and Romans. Moreover, seven furnaces were discovered at the site and these, according to the archaeologists, are an indication of the possibility that the site might have been a textile unit and settlers in the region might have been involved in industrial activities.

Keezhadi findings places the Sangam age to an even earlier period starting from 6th century BC. As per Amarnath Ramakrishna, who led the first two phases of excavations, Keezhadi site was one among the 100 sites of possible human habitation shortlisted for excavation. Discovery of Tamil Brahmi inscriptions and graffiti that date back to earliest times as compared to any other findings in India. Quite obviously, Keezhadi points to the potential of a huge trading and manufacturing habitation and a distinct civilization – the Tamil Vaigai River Valley Civilisation. The Sangam literature is rich and a huge treasure trove of information that needs to be researched extensively.

Picture: Australian seaboard, Statue of Garuda and Tamil Inscriptions, symbolising maritime culture – Credit: ancient-origins.net

Maritime Trade in Tamilakam: A Core Activity

Several artefacts with Tamil Brahmi inscriptions have been excavated in foreign countries as well. In Thailand, potsherd with Brahmi inscriptions were unearthed. Likewise, Cheena Kazhakam ( Chinese gold coins) were discovered in Srivijaya (modern day Sumatra in Indonesia) and Kadaram (modern day Kedah in Malaysia), places which were under the occupation of the Cholas.

The aforementioned evidence when correlated with the inscriptional evidence, found in foreign lands about Tamil trading settlements, will help in the historical reconstruction of the maritime trade links of Ancient Tamilakam and will attest to the extensive nature of trade carried out by the Tamils during the Sangam age.

References

Mukund, Kanakalatha. The Trading World of the Tamil Merchant: Evolution of Merchant Capitalism in the Coromandel. Orient Blackswan, 1999. https://books.google.co.in/books?id=tjXdDYChdGsC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Mukund, Kanakalatha. The World of the Tamil Merchants. Portfolio Books Limited, 2015. https://books.google.co.in/books?id=Bha2eLqMPWcC&lpg=PT6&ots=tw2qDuzDlf&dq=trade during sangam age kanakalatha mukund&pg=PT5#v=onepage&q=trade during sangam age kanakalatha mukund&f=false.

“Roman Trade with India.” Roman Trade with India – New World Encyclopedia. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Roman_trade_with_India#cite_ref-31.

Kannan, Gokul. “Keezhadi Excavation Points to Vaigai River Civilisation in Sangam Period.” Deccan Chronicle. October 1, 2016. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.deccanchronicle.com/amp/nation/in-other-news/011016/keezhadi-excavation-points-to-vaigai-river-civilisation-in-sangam-period.html.

Annamalai, S. “Uncovered: Pandyas-Romans Trade Link.” The Hindu. May 16, 2017. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/archaeological-excavation-in-sivaganga-uncovers-pandya-roman-trade-links/article10879282.ece/amp

Saju, M.T. “Tamil Trade Ships That Sailed to Foreign Shores.” Times of India. March 29, 2018. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.google.com/amp/s/timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/tracking-indian-communities/tamil-trade-ships-that-sailed-to-foreign-shore

Main Image: Keezhadi Excavation Site – Credit – ASI