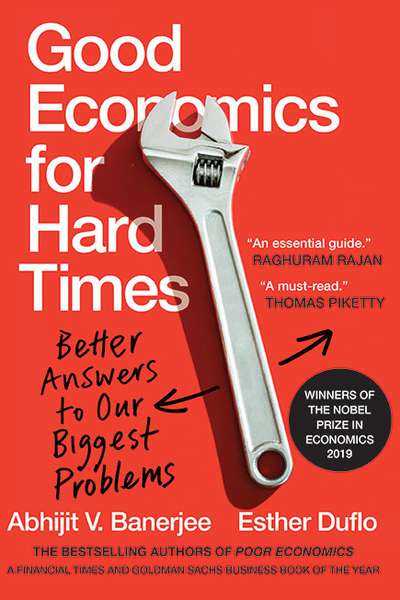

Title : Good Economics for Hard Times

By Esther Duflo and Abhijit Bannerjee

Published by Public Affairs, Hachette Book Group, New York

Year : November 2019Honesty is a quality seldom found among economists. More often than not, economists refuse to acknowledge the limitations of economic models that rely on, at times, completely unrealistic assumptions. That is, fortunately, not the case with this book. This book does not over-simplify economic issues and makes a compelling argument against making sweeping generalizations in a profession that relies on studying human behaviour.

One of the best things about this book is its accessibility, it is as accessible to a layman as it is to a seasoned economist. This book, in a significant departure from their first book Poor Economics, focuses on the burning issues of wealthy countries instead. The writing is witty and succinct, full of interesting personal anecdotes.

They start with the politically sensitive issue of immigration and show why conventional models of supply and demand don’t work for labour markets. Conventional theory, and critics of immigration, would have us believe that an influx of immigrants would drive down wages in the area and result in job losses for the natives. But Banerjee and Duflo show that the immigrants don’t just increase the labour force, they’re also consumers. Thus, they increase demand and by extension, employment and GDP in the area. They also point out that there is no strong evidence that even large influxes impact wages severely.

However, when it comes to growth they’re not as clear as they are about the impact of immigration. They make a case as to why nobody really knows what drives growth in the long term and why prominent growth economists (Sollow, Romer etc) were all right as well as wrong at the same time. According to them, both the optimists and pessimists make sound arguments and it is impossible to predict if growth will continue or perish given the humongous number of variables involved and the sheer unpredictability of technology.

Their support for free trade, unsurprisingly, is not unconditional. They don’t think it is the panacea that the neo-liberal discourse makes it out to be. Expansion of trade, they believe, is the driver of despair globally because of its random behaviour as they write, “Trade has created a more volatile world where jobs suddenly vanish only to turn up a thousand miles away.” They also present evidence showing that, at times, free trade has done more harm than good and argue that the state must provide proper support to the losers from trade if they want to mitigate the damage.

Cutting tax rates for the rich has long been argued as a certain method to improve growth by many economists. Banerjee and Duflo, however, disagree. They write “In a policy world that has mostly abandoned reason … let’s be clear: Tax cuts for the wealthy do not produce economic growth.” They argue that even the (in)famous Reagan-Thatcher era tax cuts did little to revive growth. Instead, those tax cuts, accompanied by cuts in welfare spending contributed immensely to income inequality. Advocates of tax cuts often argue that raising taxes stifle innovation, but that is clearly false as Bill Gates himself argues here.

Where a lot of economists fail and they excel, is bringing the social science aspect into economics. They don’t see people just as means to an end (growth) and emphasize on prioritising non-economic goals that don’t necessarily result into higher growth but instead improve overall happiness, dignity, self-respect and give people a sense of purpose. According to them, in this growing environment of despair, it is important to provide people with a sense of purpose.

They argue, quite successfully, that we should change our policy response to poverty and stop letting only poverty define poor people. They recommend that poor people be seen just like normal people who have dreams and desires and policymakers need to stop believing that they know better about what poor people need than the people themselves.

Lastly, they say that the message of policy interventions should not be ‘you are being rescued by the state’ and instead ‘this is the state’s support to ensure you have the basic rights you deserve.’ It is vital that they’re given the respect they deserve if we want them to lead dignified lives and not make them feel like they’re living on handouts from the state as even the needy hate being dependent on others. Restoring the dignity of the poor is an important step in eradicating poverty, they say.

This book’s brilliance, in my opinion, is evident from the fact that economists across the ideological spectrum, from Sollow to Piketty, are all in awe of this work of art. To be honest, I have learnt more about economics and policymaking from this book than I did as an economics graduate.

The arguments put forth in this book were, to an extent, eye-opening for me. I found them compelling and I believe you will too.

Mohit Verma is a Research Intern in TPF. He is pursuing his Masters at the Madras School of Economics (MSE), Chennai.