This research paper was originally published in the “African Journal of Terrorism and Insurgency Research (AJoTIR)”, Volume 2, Number 1, April 2021. Pp. 89-106.

Abstract

We often find the application of indistinctive, brutal and extraordinary violence by all fighters and soldiers in terrorist, insurgency, and counter-insurgency acts in Africa. This article argues that we need a code of honour for those bearing arms to limit these unrestricted acts of violence, a code of honour that combines military duties with the demands of civil society in the model democratic warrior. The changes to the global system that followed the end of the Cold War are widely regarded as requiring a different kind of soldier for democratic societies. A number of writers have proposed that the new model should be that of the “warrior,” a concept that highlights the psychological and social distinctiveness of those who bear arms. Such men and (rarely) women are often conceived as operating according to a distinctive code of honour that sets them apart from civil society, usually in a positive way. But we know that the concept of honour may also lead to a terrible escalation. So, the task is to reconnect the concepts—warrior and honour—to civil society to de-escalate the ongoing brutal violence in civil wars. There is no honour in killing innocent people. On the contrary, it is perhaps the most egregious act against one’s honour and dignity to torture, violate, or kill the innocent. The concept of the democratic warrior seeks to reinstate honour and dignity to those bearing arms.Keywords: democracy, warrior, civil society, civil war, honour, dignity, terrorism, Clausewitz, wondrous trinity, containing violence.

Introduction

At first glance, the concept of the democratic warrior appears contradictory. Indeed, it combines seemingly conflicting value systems in a single concept. Like a magnet or Clausewitz’s favoured model of the unity of polar opposition between attack and defence, a methodology can be formulated to explain how this type of conflicted unity is not necessarily a logical opposition and can be a dynamic interrelationship on a continuum. At one end of the continuum is democratic equality and non-violent conflict resolution, while at the other end is the threat of (and sometimes) violently enforced limitation of war and violence; at one end is a civilized society, while at the other is a subsystem of society whose identity is defined by martial honour.

The decisive bond that can link the two poles of this dynamic relationship, without eliminating their opposition, is the classical republican virtues, which can lay claim to relative validity in both spheres. Since Plato, the classical virtues have been prudence (wisdom), justice, fortitude, and temperance. Without a specific ethos aimed at the political functioning of the polity, a state can sustain itself only under the conditions of a dictatorship. If republican virtue, which is oriented toward the polity, cannot be directly reconciled with liberal democracy and its focus on the individual, it can take on a completely new significance as a bond linking a democratic society to democratic warriors. For Machiavelli, republican virtue already guarantees both external and internal freedom. In this respect, the necessary though not yet adequate condition of the democratic warrior is to also be a republican soldier. Add to this the limitation of war and violence in a global society to make democratic societies possible. A renewal of the republican virtue is the link between a liberal-democratic society and a warrior ethos.

The “warrior” is by definition someone who chooses to bear arms and is proficient in their use. In this sense, whatever the distinctive characteristics of the warrior ethos, its institutionalization reflects the same preferences for professionalism, expertise, and individualism that are characteristic of modern society as a whole. Contemporary conditions, it is argued, no longer call for armed masses, but for experts whose willingness to serve in uniform will allow others the freedom not to serve.

It must be admitted, however, that the concept of the warrior does not call forth associations with modernity, but rather of the “archaic combatant” (Röhl 2005), whose ethos, skills, and experiences set him apart from normal society and in opposition to its basic values, of which the most cherished is, of course, peace. The fact the warrior freely chooses his profession may be consistent with democratic values, but the existence of a “warrior class” uniquely skilled in the use of force, whose values are not those of society as a whole, is scarcely consistent with democratic interests. It is also true that those who serve in today’s democratic armies are called upon to do a great deal more than fight. Although phrases like “armed social worker” undervalue and denigrate the martial qualities that remain foundational to military life, it is true that only a small percentage of men and women in uniform actually fight, and that their duties entail a wide range of activities in which violence plays no part. To those who wish to uphold the warrior spirit, the diverse requirements of modern military missions are liable to hold scant appeal, which may undermine the sense of purpose and identity that drew them to the profession in the first place.

The discussion that follows seeks to build a bridge between the distinctive ethos of the warrior and the moral and political requirements of democratic societies, using the concept of the “democratic warrior.” It seeks to do justice to the self-image of those who bear arms (a morally distinctive task) while connecting it to the various goals and practices of democratic societies, and the diverse uses to which they put their armed forces. We may begin by noting that a warrior, even in the most traditional terms, is not merely a combatant—a fighter—but has always performed and embodied a range of social, military, and political roles. Our starting point for considering what those roles must be is Clausewitz’s concept of the trinity, a metaphor intended to encompass all types of war, which, by extension, can provide a lens through which the ideal range of characteristics required of the democratic warrior can be envisioned. War itself, as Clausewitz avers, is compounded of primordial passions, an irreducible element of chance, and what he called an element of “subordination” to reason, by which its instrumental character is revealed. When Clausewitz set forth his trinity, he posited that the chief concern of the warrior must be the mastery of chance through intelligence and creativity; and so it remains. Yet there is no reason to suppose that such mastery means that war’s social and political requirements should be ignored. On the contrary, unless they too are mastered, the warriors sent forth by democratic societies cannot represent the values and interests of the communities that depend on them, and of which they remain apart (Herberg-Rothe 2007).

Soldiers and Warriors

In both German and English, the word “soldier” (soldat) originally referred to a paid man-at-arms. The term became common in early modern Europe and distinguished those who were paid to fight— primarily in the service of the increasingly powerful territorial states that were then coming to dominate the continent—from members of militias, criminal gangs, volunteer constabulary and local self-defence forces, and other forms of vernacular military organizations. The rise of the soldier was linked to the rise of the state. This connection distinguished him from the “mercenary,” who also fought for pay, but as a private entrepreneur, what we would today call a “contractor.” Standing armies comprised of soldiers were different from and militarily superior to, the feudal hosts of the past, whose fighters served out of customary social obligation and generally possessed neither the discipline nor the martial proficiency that the soldier embodied. Clausewitz highlights these developments briefly in the last book of On War, and portrays them as an advance in political organization and military efficiency (Clausewitz 1984, 587-91).

The absolute monarchies that made the paid soldier the standard of military excellence in early modern Europe were generally indifferent to the social and political identities of those they paid to fight, though not always. Frederick the Great, for instance, lamented his reliance on foreign troops and believed that his own subjects made better soldiers. “With such troops,” he wrote, “one might defeat the entire world, were not victories as fatal to them as to their enemies” (quoted in Moran 2003, 49). It was, however, only with the French Revolution that a firm expectation was established that a soldier bore arms not merely for pay, but out of personal loyalty to the state, an identity that was in turn supposed to improve his performance on the battlefield. This connection, needless to say, was largely mythical. Most of the men who fought in the armies of the Revolution, and all major European wars since then, are conscripts who would not have chosen to bear arms on behalf of the state if the law had not compelled them to do so. Nevertheless, submission to conscription was itself regarded as an expression of the ideal of citizenship, a concept that, like honour, depends upon the internalization and subjective acceptance by individuals of norms arising within the larger society.

The French Republic never referred to its soldiers as conscripts, always as volunteers. The success of its armies and those of Napoleon, although transient, insured that “defence of the Fatherland [became] the foundation myth of modern armies”(Sikora 2002). The myth of voluntary sacrifice by the “citizen-soldier” to defend the community proved central to the legitimization of conscript armies, even in societies where democratic values were slow to emerge. In the middle of the nineteenth century, as Frederick Engels observed, conscription was Prussia’s only democratic institution (Frevert 1997, 21).

It had been introduced in reaction to Prussia’s defeat by Napoleon, whose triumph was owed to the fact that the resources of the entire French nation were at his disposal. The aim of the Prussian military reforms was to accomplish a similar mobilization of social energy for war, but without inciting the revolutionary transformation of society that had made such mobilization possible in France. Prussia was no sovereign nation of citizens, and while the reform of its armed forces helped it to regain its position among the leading states of Europe, their political effect was limited.

Many of those who promoted reform, including Clausewitz, hoped conscription would contribute to the democratization of Prussia’s armed forces, and, indirectly, of society as a whole. But the moral influence could as easily run the other way, and, as Friedrich Meinecke observed, measures designed to bind army and society together had the effect, in Prussia, of militarizing society instead. Even the Great War did not fully succeed in stripping war of its moral glamour. The supposedly heroic massacre of German troops attacking the British at Langemarck (1914), for instance, remained a staple of right-wing mythology until the end of the Third Reich, by which “our grief for the bold dead is so splendidly surpassed by the pride in how well they knew how to fight and die (Hüppauf, 1993, 56). Alongside this kind of blood-drenched nostalgia, the industrialized warfare exemplified by battles like Verdun (1916) also asserted themselves. Under these circumstances, fighting and dying well acquired some of the aspects of industrialized labour, in which a soldier’s duty expresses itself, not through the mastery of chance as Clausewitz proposed, but through submission to what Ernst Jüngercalled “the storm of steel.”

It was only after World War II that German soldiers became authentically democratic citizens in uniform. According to Wilfried von Bredow, the creation of the Bundeswehr in 1956 was “one of the Federal Republic of Germany’s most innovative and creative political reforms, fully comparable in its significance to the conception of the social market economy” (Bredow 2000). Its evolution as an integral part of German society has embodied a calculated break with the German past, one that has become even more apparent since the demise of the Soviet Union has shifted the mission of the German army away from national defence and toward expeditionary operations calculated to help maintain regional and global order. As the conscript armies of the past have given way to the professional and volunteer armies of the present, in Germany and elsewhere, the model of the democratic “citizen in uniform” has once again been required to adapt to new conditions.

It is perhaps slightly paradoxical that as wars have become smaller and more marginal in relation to society as a whole, the ideal of the warrior as an apolitical professional fighter has regained some of its old prominences. Such individuals are thought to embody values different than those of society as a whole, to the point where their loyalties, like their special capabilities in battle, are thought to spring solely from their organization and mutual affiliation. John Keegan, a proponent of the new warrior, explains the rejection of the values of civil society in terms of the psychological impact of violence on those who experience and employ it. War, Keegan argues, reaches into the most secret depths of the human heart, where the ego eliminates rational goals, where pride reigns, where emotions have the upper hand, and instinct rules. One of Keegan’s models of the warrior is the Roman centurion. These officers were soldiers through and through. They entertained no expectation of rising to the governing class, their ambitions were entirely limited to those of success within what could be perceived, for the first time in history, as an esteemed and self-sufficient profession. The values of the Romans professional soldier have not diminished with the passage of time: pride in a distinctly masculine way of life, the good opinion of comrades, satisfaction in the tokens of professional success, and the expectation of an honourable discharge and retirement remain the benchmarks of the warrior’s life (Keegan 1995, 389-391).

The enthusiasm of Keegan and others for the revival of the warrior ethos is the belief that “honour” can play an important role in limiting violence, far more effective than the proliferation of legal norms that lack the binding psychological validity required to stay the hand of those who actually take life and risk their own. Warriors use force within a customary framework of mutual respect for one another. This is part of what has always been meant by “conventional warfare”, a form of fighting that necessarily includes a dissociation from combatants considered to be illegitimate. How and whether these kinds of customary restraints can be successfully reasserted under contemporary conditions is one of the central problems with which the concept of the democratic warrior must contend. In opposition to Keegan, I think, that the warriors’ code of honour must be related back to civil society, although this is a task which requires bridging a gap and remains a kind of hybrid.

Old and New Wars

To judge what kind of “weapon carrier” will be needed in the twenty-first century, we must begin by looking at developments since the end of the East-West conflict. It has proven, broadly speaking, to be a period of rapid social, political, and economic development whose outstanding characteristics are marked by the decline or disappearance of familiar frameworks and inherited values. Thus, one speaks of denationalization, de-politicization, de-militarization, de-civilization, de-territorialization, and delimitation.

Unsurprisingly, these changes are also supposed to be marked by “new” wars, characterized by the decline of statehood, the rise of privatized violence, the development of civil war economies, and the reappearance of types of combatants thought to be long gone— mercenaries, child soldiers, warlords, and so on. The new types of combatants are in turn associated with rising incidences of suicide bombing, massacre, and other forms of atavistic and irrational violence(Kaldor 1999, Münkler 2004).

Political and academic discourses have produced a range of new concepts designed to capture these conditions, including privatized war, asymmetrical warfare, small wars, wild wars, low-intensity conflict, post-national wars; wars of globalization on the one hand, and of “global fragmentation” on the other. It is apparent, however, that each of these terms describes only one segment of a complex reality. To some extent, a new type of war is being discovered with each new war. At the same time, these different terms share a common assumption that war now consists mainly of conflicts involving non-state actors on at least one side, and, by extension, that the motivation and goals of such belligerents are likely to prove unfathomable in political terms. The result for some is an approaching anarchy (Kaplan 1994), whose remedy is a revived liberal interventionism, the only principle that seems able to guarantee a modicum of global order (Münkler 2007).

It is possible, however, that the contemporary diffusion of conflict beyond the confines of the state system is no more than a transitional phase, with particular strong links to those parts of the world—Africa and Central Asia above all—where the challenges of post-imperial social and political adaptation are still especially pronounced. Neither does the fact that the parties to war are non-state actors necessarily mean that such wars lack a political or ideological basis. Such wars may not represent a clash between order and anarchy but between competing conceptions of order (Münkler 2004). While a revived interventionism may indeed be a suitable antidote to anarchy, it is unlikely to do more than aggravate indigenous conflicts over the politics of order – and as it seems at present, it is contributing to the escalation of violence throughout the world. Now, as in the past, violence is not simply a source of disorder. It is also a means of shaping order and providing the basis for community formation.

It is possible to wonder, in other words, how new the “new wars” actually are. Widespread atavistic and vernacular violence were already prominent features of the Chinese civil war, the Russian civil war, the Armenian genocide, and many other episodes of “old wars”. Those who favour the concept note a number of formal changes that resulted from the disappearance of Soviet-American rivalry, above all a decline in external assistance. The proxy wars of the past have become the civil wars of the present, conducted by parties that must rely on their own efforts to obtain the necessary resources, including illegal trafficking in diamonds, drugs, and women; brutal exploitation of the population; extreme violence as a way of attracting humanitarian assistance that can then be plundered; and the violent acquisition of particularly valuable resources (robber capitalism). These changes may well amplify the social consequences of violence, but do not necessarily deprive it of its instrumental and political character (Schlichte 2006).

The point of departure for the study by Isabelle Duyvesteyn, for example, is a very broad definition of politics based on Robert Dahl: “any persistent pattern of human relationship that involves, to a significant extent, power, rule or authority” (Duyvesteyn 2005, 9). Duyvesteyn refers especially to the fact that in the fast-developing states she has studied, the differences between economics and politics are not as clear cut as Westerners expect. Struggles that seem to be about the acquisition of resources can be motivated by power politics to obtain a separate constituency. Because the position of power in these conflicts is often determined by the reputation of the leader, what may appear to be personal issues can also be incorporated into a power-political context. Her hypothesis is not that economically, religiously, ethnically, or tribally defined conflicts are masks for politics, but rather that these conflicts remain embedded in a political framework that is understandable to the participants.

It is also apparent today’s civil wars do not always trend irrevocably toward social and political fragmentation, becoming increasingly privatized until they reach the smallest possible communities, which are held together by only violence itself. The defeat of the Soviets in Afghanistan, for instance, gave rise to a civil war between warlords and individual tribes that appeared to be tending in this direction for a time, only to acquire a new and recognizably ideological shape once the Taliban seized power. This new tendency was confirmed by the Talibans’ willingness to give shelter to al-Qaeda, a global and trans-national organization of almost unlimited ambition, whose attacks upon the United States have in turn embroiled Afghanistan in a conflict about the world order pitting the West against militant Islam. At present, we witness in “Sahelistan” a similar development, but this is not confined to a single state, but to the whole region.

At a minimum, it seems clear that the new wars, to the extent that they are new, are not all new in the same way. In some, violence does indeed appear to gravitate downwards towards privatized war; in others, however, the movement is upwards, towards supra-state wars of world order. Although these trends are linked in practice, analytically they are distinct. States do still wage wars, but for the most part, they are now doing so not in pursuit of their own particular interests but for reasons related to world order. This is what accounts for the new interest in an American empire and hegemony (Walzer 2003). Nor is America the only state capable of seeking and exercising global influence.

Russia, China, India and Europe (whose superficial fragmentation masks its concerted economic, regulatory and power-political influence) are all capable of challenging American influence in particular spheres of activity; and one day they may do so in all spheres (Zakaria 2009). In any event, the use of force by strong states in pursuit of world order, whether cooperatively or competitively, is likely to remain the dominant strategic reality for some time to come; a fact that should not be obscured by the simultaneous proliferation of privatized violence on the periphery of the world system.

Clausewitz’s Trinity as a Coordinate System

The argument about the newness of new wars is also an argument about the continuing salience of Clausewitz’s understanding of war as, in his words, a “wondrous trinity,” by which primordial violence and the exigencies of combat may finally be subjugated to reason and politics. It is apparent, however, that while the proportions of these three elements may vary, a good deal nowadays, perhaps more so than in some periods in the past, they do not escape the theoretical framework that Clausewitz established. At the same time, his trinity points us towards the essential characteristics of the “democratic warrior,” whose success requires that he masters the multiple sources of tensions that Clausewitz detected in the nature of war itself.

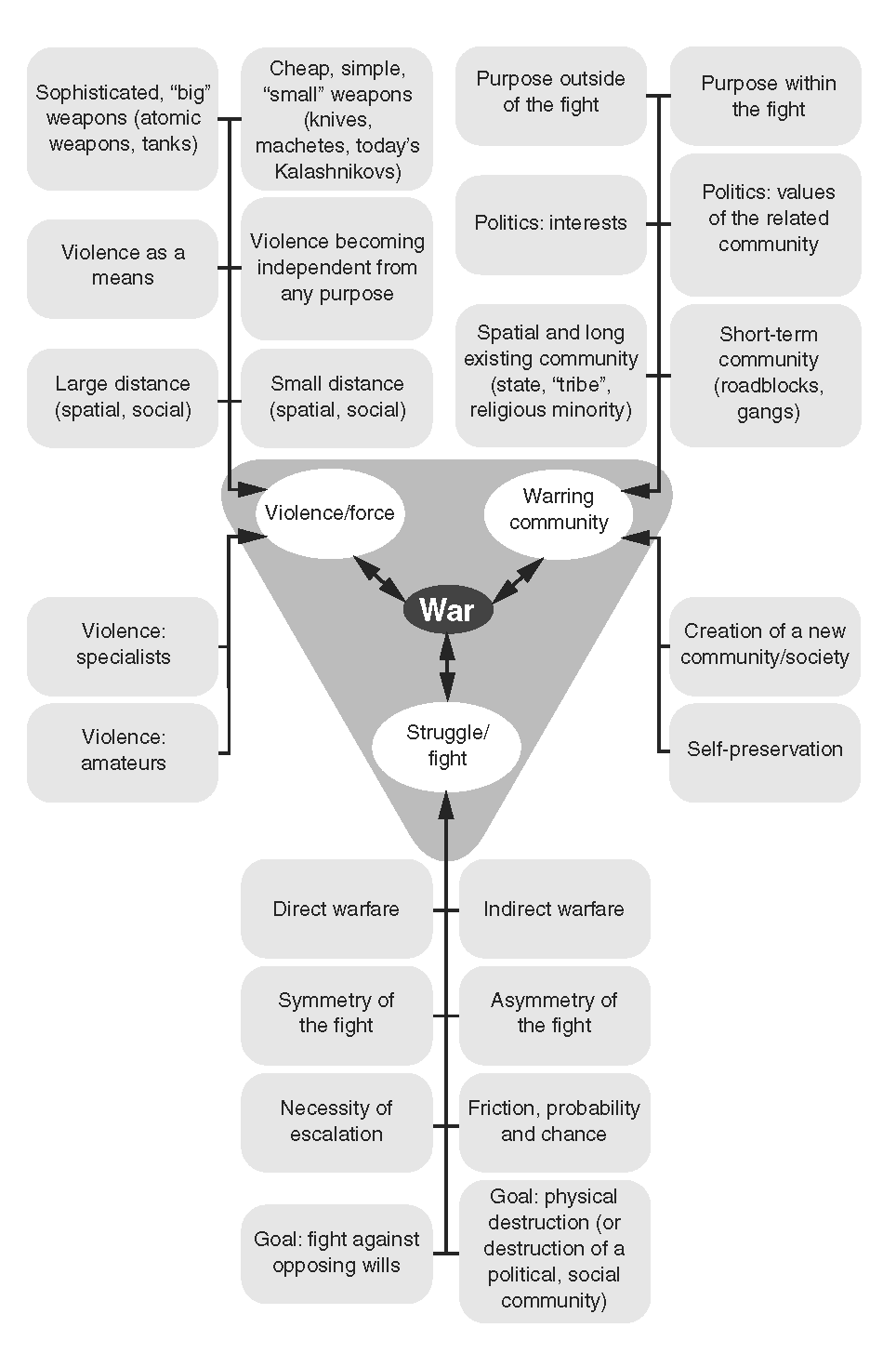

Clausewitz’s trinity present war as embodying three elements in constant tension with each other: primordial violence, the fuel on which war feeds; the fight between two or more opponents, by which violence is given military effective form; and the community, whose interests, as represented by policy, give war its purpose, and whose existence provides the soldier with his essential identity: as one who fights for something larger than himself. The shifting proportions among these elements that modern war continues to display would not have surprised Clausewitz. On the contrary, he knew that all three would always be present in every war and that a “theory that ignores any one of them . . . would conflict with reality to such an extent that for this reason alone it would be totally useless” (Clausewitz, On War, 1984, 89; see Herberg-Rothe 2007). Each requires exploration if the characteristics of the democratic warrior are to be understood.

Violence and force

The most crucial polarity in Clausewitz’s trinity is between the instrumentality of war and the autonomy of violence. Clausewitz noted the tendency of violence to become absolute, and therefore an end in itself, a tendency that was restrained both by the instrumental rationality of policy and, less obviously perhaps, by the skill of the combatants. Clausewitz also notes the paradoxical influences that can attend the use of force at a distance. If combatants are separated from each other in space and time, it may promote relative rationality in the use of force; or it may not, since it introduces the disinhibiting influence of impersonal killing, in which the humanity of the opponent is no longer perceived. Fighting “face-to-face” demands personal aggressiveness and even hatred, which can lead to increasing ferocity in the use of force. At the same time, however, it may make it easier to perceive the opponent as human. A similarly paradoxical logic may arise from the use of expensive weapons versus simple ones. Expensive weapons systems and the highly trained combatants required to use them can lead to a certain limitation of war because these cannot be so easily risked (as was the case, he argued, in the wars of the 18th century). In contrast, wars waged by relatively unskilled combatants employing cheap and simple weapons may be more likely to escalate – as is evident from many of the civil wars in Africa, particularly with child soldiers.

The Fight

The most basic reason that the violence of war is prone to escalate is that combatants share a common interest in not being destroyed. In most other respects, however, their interaction is asymmetrical, most profoundly so, as Clausewitz says, in the contrasting aims and methods of attack and defence, which he avers are two very different things. The shape of combat is also influenced by whether war is directed against the opposing will (in effect, a war to change the adversary’s mind)or if it aims at his “destruction.” Clausewitz specifies that by the destruction of the opposing armed forces, he simply means reducing them to such a condition that they can no longer continue the fight. Nevertheless, Clausewitz long favoredNapoleon’s approach to warfare, which emphasized direct attack against the main forces of the enemy. Other forms of fighting are also possible, however, whose aim is to exhaust the enemy’s patience or resources indirectly, rather than confront and defeat his armed forces in the field. The real war, in Clausewitz’s days and in ours, is generally a combination of direct and indirect methods, whose proportions will vary with the interests at stake and the resources available.

Warring Communities

When referring to warring communities, we must first differentiate between relatively new communities and those of long-standing. This is because in newly constructed communities, recourse to fighting is liable to play a greater relative role in its relations with adversaries; whereas, in the case of long-standing communities, additional factors come into play. Clausewitz argues that the length of time a group of communities has existed significantly reduces the tendency for escalation because their long-standing interactions will include elements other than war, and each party envision the other’s continued existence once peace is made, a consideration that may moderate the use of force.

War’s character will also vary depending on whether it aims to preserve the existence of a community or, as in revolutionary crises, to form a new one; whether war is waged in the pursuit of interests, or to maintain and spread the values, norms, and ideals of the particular community (see Herberg-Rothe 2007). Closely related to this contrast, although not exactly congruent with it, is the question of whether the purpose of war lies outside itself or, especially in warring cultures, whether the violence of the fight has independent cultural significance. The social composition of each society and the formal composition of its armed forces (regular armies, conscripts, mercenaries, militias, etc), play an important role here. Summarizing these fundamental differences yields the coordinate system of war and violence shown in the diagram.

Every war is accordingly defined in terms of its three essential dimensions: violence, combat, and the affiliation of the combatants with a community on whose behalf the combatants act. Historically, these three tendencies within the “wondrous trinity” display almost infinite combinations and multiple, cross-cutting tensions since every war is waged differently. Thus, every war has symmetrical and asymmetrical tendencies, for instance, even when it may appear that only one of these tendencies comes to the fore (Herberg-Rothe 2007).

The tension between the coordinates of Clausewitz’s trinity may also be heightened by different forms of military organization. Those that feature strict hierarchies of command are perhaps most conducive to the transmission of political guidance to operating forces; whereas what is today called network-centric warfare is characterized by loose and diffuse organizational structures, in which the community’s political will and mandate can no longer be so readily imposed on combatants directly engaged with the enemy. As in the warfare of partisans, networked military organizations place a high value on the political understanding of the individual soldier. It is because of the relative independence of soldiers in network-centric warfare that this type of warfare does not require an “archaic combatant,” but a democratic warrior who has fully internalized the norms of the community for which he fights.

The Democratic Warrior in the Twenty-first Century

Even in Clausewitz’s day, war was not the only instrument of policy that state’s possessed, though it was undoubtedly the most central. Today, its centrality is less obvious, even as the complexity of its connections to other forms of state power has increased (Thiele 2009). Combining the different perspectives afforded by foreign, economic, developmental, judicial, domestic, and defence policy permits a global approach to conflict resolution while making the considerations surrounding the use of force more complicated than ever. States now pursue their security through many avenues at once, and all the agencies involved must consciously coordinate, connect, and systematically integrate their goals, processes, structures, and capabilities.

Given the continuing expansion of the concept of security in recent years, a democratic army needs a specific task and function since its essential purpose—the use of force—can not be dispensed with. There have been those who thought it might be. When the East-West conflict ended, Francis Fukuyama announced the “end of history,” meaning an end to the practice of war and violence (Fukuyama 1992). The triumphant advance of democracy and free markets seemed unstoppable, to the point where it appeared as if the twenty-first century would be an age defined by economics and thus, to a large extent, by peace. These expectations have now been decisively overturned by ongoing massacres and genocide in Africa; by the return of war in Europe (as happened in the former Yugoslavia); by the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States and, the subsequent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq; the war between Georgia and Russia over South Ossetia in 2008, the civil war in Syria and Iraq and finally the prospect of war to suppress Iran’s nuclear program (itself a profoundly dangerous and destabilizing step, should it become reality).

In a complete reversal of Fukuyama’s thesis, a struggle against a new brand of Islamic totalitarianism appears to have begun, in which violence has become “unbounded”—because terrorist attacks are potentially ever-present because no end to them is in sight and there is no reason to assume there is any limit to the scale of violence terrorists might employ, including the use of nuclear weapons should they come to possess them. These processes of growing disinhibition must be countered by a new containment policy that limits the expansion of war and violence in the world.

Two basic assumptions underlie this conception. The first is that the escalation of violence in world society is so multifaceted and differentiated that a single counter-strategy will not suffice. Rather, an overarching perspective is required to decide which measures are suitable in individual cases—without being able to exclude the possibility of terrible errors and miscalculations. The second assumption is that in today’s global society—as has been the case throughout history—many contrary processes are at work. Thus, regard for only one counter-strategy can have paradoxical, unanticipated consequences.

This can be clarified using the example of democratization. If a general effort at worldwide democratization was the only counter-strategy against the disinhibition of violence and war, the results would almost certainly be counterproductive, not least because the spreading of democracy might itself be a violent process. A one-sided demand for democratic reform without regard for local conditions might, in individual cases, contribute to the creation of anti-democratic movements. The historical experience bears this out. After the First World War, nearly all of the defeated states underwent an initial process of democratization under the tutelage and supervision of the victors. Yet, almost all ended in authoritarian or even totalitarian regimes.

Thus, the concept of the democratic warrior is not based on imposing democracy by force, but on limiting war and violence to enable the organic development of democratic self-determination. A differentiated counter-strategy of curbing war and violence in the world, with a view to fostering good governance (as a first step toward democratic governance), is the common element shared by humanitarian intervention and the development of a culture of civil conflict management. To this must be added measures to limit the causes of war and violence, such as poverty, oppression, and ignorance. Last but not least, this new form of containment requires effective restraint not just in the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, but also of small arms, which continue to kill far more people than any other kind of arms.

The containment of violence does not mean there will be entirely non-violent societies, much less a non-violent world society, in the foreseeable future. All else aside, the goal of completely eliminating violent conflict would ignore the fact that historically speaking, conflicts and their resolution have often furthered human development toward free and democratic ideals—as per the American struggle for independence and the French Revolution. The primary task of politics in the twenty-first century is therefore to radically limit violence and war so that non-violent structures and the mechanisms of the “social world” can have an impact. In this context, democratic warriors have a unique role to play; not as those who impose democracy by force, but as those who make diverse forms of culturally authentic self-determination possible, by curbing and containing war and violence.

Conclusion

It must be repeated, the concept of the democratic warrior appears to be contradictory. Indeed, it combines contradictory value systems in a single concept. Nevertheless, to adopt the metaphor favoured by Clausewitz (Herberg-Rothe 2007), the elements of tension in the democratic warrior’s identity can be conceived as the poles of a magnet, whose mutual opposition is not an illusion but is nevertheless a means to a larger, unitary end. It is what creates the magnet: the north pole of a magnet cannot exist alone. At one end of the continuum of the democratic warrior’s identity lies the values of democratic equality and non-violent conflict resolution; at the other, the realization that force itself may sometimes be necessary to limit war. At one end, is a civilized society, and at the other a subsystem of that same society, whose identity is defined by traditional concepts of honour and martial valour.

As observed at the beginning of this essay, the bonds that link the two poles of this relationship, without eliminating their opposition, are the classical republican virtues, which lay claim to validity in both spheres. It was Plato who defined the classical virtues as intelligence, justice, fortitude, and temperance, which is also are characteristics in the Confucian tradition (Piper 1998 concerning Plato). Without them, a state can sustain itself only under dictatorship. With them, both external and internal freedoms are possible (Llanque 2008). They are the keys to the democratic warrior’s identity, providing the crucial link between the values of liberal-democratic society and those other values—courage, loyalty, self-sacrifice—that have always set the warrior apart.

References

Bredow, Wilfried von (2000), Demokratie und Streitkräfte (Wiesbaden: VS publishers, 2000).

Clausewitz, Carl von (1984), On War. Ed. by Peter Paret and Michael Howard (Oxford: OUP).

Duyvesteyn, Isabelle (2005), Clausewitz and African War (London: Routledge).

Frevert, Ute (1997), Die kasernierte Nation (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2001).

Frevert, Ute(ed.), (1997), Militär und Gesellschaft im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert

(Stuttgart: Klett–Cotta).

Fukuyama Francis (1992), The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press).

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2007), Clausewitz’s puzzle (Oxford: OUP). Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2017), Der Krieg. 2.Edition. (Frankfurt:

Campus).

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas and Son, Key-young (2019), Order wars and floating balance. How the rising powers are reshaping our world view in the twenty-first century (New York: Routledge).

Hüppauf, Bernd (1993), “Schlachtenmythen und die Konstruktion des ‘Neuen Menschen’,” in Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch . . . : Erlebnis und Wirkung des ersten Weltkrieges, ed. Gerhard Hirschfeld, et al. (Essen: Klartext, 1993).

Llanque, Marcus (2008) Politische Ideengeschichte. Ein Gewebe politischer Diskurse (Munich: Oldenbourg.

Kaldor, Mary (1999), New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era

(Stanford: Stanford University Press).

Kaplan, Robert (1994), “The Coming Anarchy.”In: Atlantic Monthly no.

273, 44–76.

Keegan, John (1995), Kultur des Krieges (Berlin: Rowohlt).

Kuemmel, Gerhard (2005), Streitkräfte im Einsatz: Zur Soziologie militärischer Interventionen (Baden-Baden: Nomos).

Moran, Daniel (2003), “Arms and the Concert: The Nation in Arms and the Dilemmas of German Liberalism,” in The People in Arms: Military Myth and National Mobilization since the French Revolution, ed. Daniel Moran and Arthur Waldron(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Münkler, Herfried (2004), The New Wars (New York: Policy). Münkler, Herfried (2007), Empires (Cambridge:Polity Press).

Pieper, Josef (1998), Das Viergespann—Klugheit, Gerechtigkeit, Tapferkeit, Maß (Munich: Kösel).

Röhl, Wolfgang (2005), “Soldat sein mit Leib und Seele. Der Kämpfer als existenzielles Leitbild einer Berufsarmee in EinJob wie jeder andere. Zum Selbst- und Berufsverständnis von Soldaten, ed. Sabine Collmer and Gerhard Kümmel (Baden-Baden:Nomos, 2005) 9–21.

Schlichte, Klaus (2006), “Staatsbildung oder Staatszerfall. Zum Formwandel kriegerischer Gewalt in der Weltgesellschaft,In: ”Politische Vierteljahresschrift 47, no. 4.

Sikora, Michael (2003), “Der Söldner,” in Grenzverletzer. Figuren politischer Subversion, ed. Eva Horn, Stefan Kaufmann, and Ulrich Bröckling (Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos, 2002).

Thiele, Ralph (2009), “Trendforschung in der Bundeswehr”. In: Zeitschrift für Sicherheits- und Außenpolitik 2, 1–11.

Walzer, Michael (2003), “Is there an American Empire?” In: Dissent Magazine 1 (2003), URL; http://www.dissentmagazine.org/menutest/archives/2003/fa03/walzer.htm last accessed 16. 4. 2020.

Zakaria, Faared (2009), The Post-American World (New York: W. W. Norton).