The Covid-19 pandemic is a global catastrophe that has disrupted the economies and national health of countries and the livelihood millions across the world. In India, the impact in 2020 was presumably well controlled, and the beginning of 2021 saw the Indian government projecting prematurely the return of normalcy. This sense of normalcy led to a lowering of the precautions, and the month of April saw the rise of the second wave. The second wave was vicious, crippling the healthcare system and resulting in a huge number of deaths, primarily attributed to the shortage of oxygen supply in most states. This crisis exposed the shortcomings of the Indian healthcare system and the wide disparities that exist in access to healthcare between different sections of the society, a result of the shockingly low investment in healthcare and human resources. The catastrophe has led many to question the efficacy of the healthcare system and the level of expenditure incurred on it, and whether universal healthcare would have allowed the country to tackle these events. Analysis of the impact of universal healthcare requires insight into the structure and efficacy of healthcare in India, given our history and experiences.

The principle behind universal healthcare states that every individual who is a citizen of the country must have access to essential health services, without the obstruction of financial hardship. Among the most efficient methods of ensuring that this principle is adhered to is bringing it under the constitutional mandate. Although the Supreme court has, in its various judgements, recognized health as a fundamental right, it is not yet recognized in the constitution. Article 21 of the constitution reiterates the right to life, with the landmark judgment of Maneka Gandhi v The Union of India specifying that the article also includes the right to live a dignified life and access to all basic amenities to ensure the same. This statement has been given a new context in light of the recent crisis, in which most of the fatalities caused were due to respiratory problems caused by the virus where providing oxygen availability became an essential requirement for the cure. In such a scenario, the oxygen availability constitutes part of basic amenities, which the government failed to supply in adequate quantity. The government fulfils its obligation towards healthcare in the form of government hospitals and healthcare centres, but their situation was synonymous with the private sector. The government claims that the hospitals under their control are sufficient, but the recent predicament has proven that the aforementioned claim is not true. The healthcare services provided by the government will be meaningful only if access to such hospitals is convenient for the common people and the hospitals are well-endowed with investment and human resources. An analysis of our constitution, especially Article 21, which guarantees protection of life and personal liberty, makes it evident that the principles on which our democracy is founded dictate that healthcare is one of the most important obligations of the government, and the most efficient method for fulfilling said obligation is the introduction of Universal healthcare in India.

An attempt at examining the applicability of universal healthcare was made by the Planning Commission through the 12th Five-Year plan. The first-ever framework for universal health coverage was developed by a High-Level Expert Group, which planned to develop a system that was in accordance with the nation’s financial capabilities. The primary objective of these reforms was to reduce the out-of-pocket expenditures incurred by lower-income groups on healthcare services and increase the number of people covered under the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana. Around this time the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana was scrutinized by many due to its low enrolment rates, high transaction costs due to insurance intermediaries, and allegations that the government was using it as a pathway to hand over public funds to the private sector. The objective of reducing out-of-pocket expenditure even though expressly mentioned did not come to fruition because of the lack of extensively funded facilities, especially in rural areas which were covered by RSBY. These facilities were lacking not only in medical infrastructure but also the medicines required for treatment, which compelled the patient to bear the expenses of medicines on their own. The 12th Five-year Plan also proposed an increase in Budget allocation for health from 1.58% to 2.1% of the GDP, which was again criticized because it was very low in relation to the global median of 5%, despite the population size of the country. The healthcare reforms also failed to take note of the important role played by nutrition and the Public Distribution System in aiding the advancement of healthcare. The 12th five-year plan is not considered successful due to the poor implementation of the reforms introduced and provides valuable lessons for the implementation of universal healthcare coverage in the future.

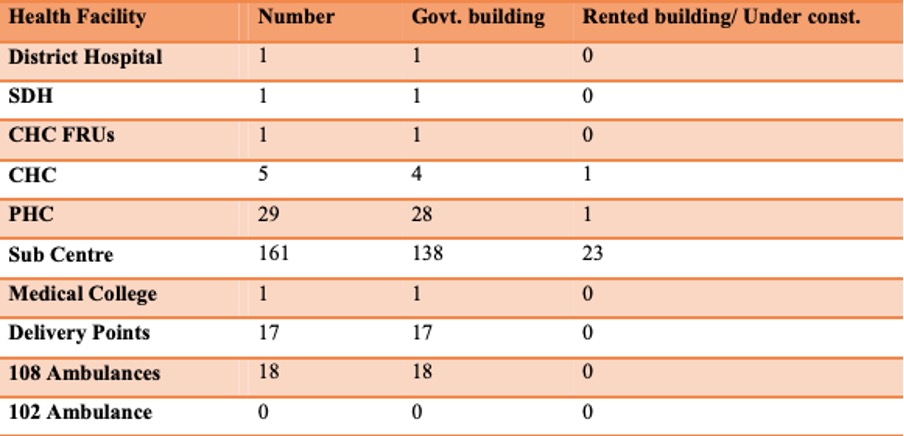

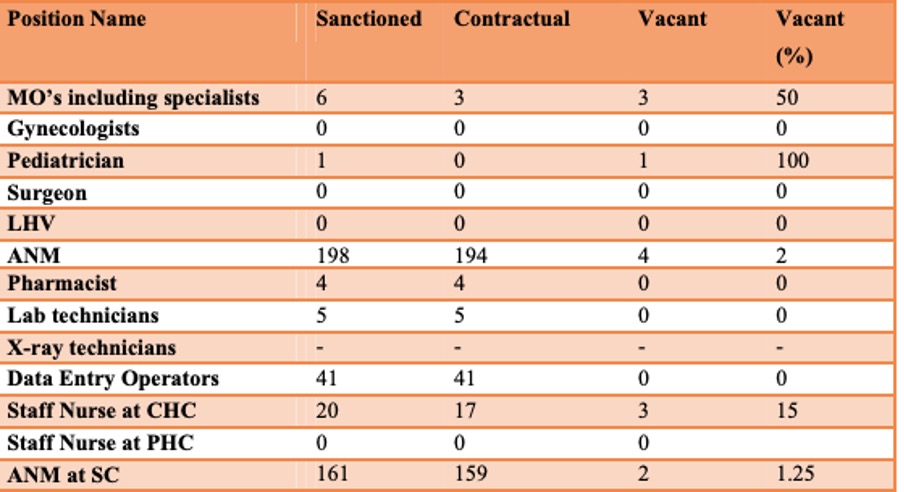

The need for implementation of universal healthcare coverage can be made evident through a case study of the town of Sonipat, which is near Delhi and is a rural area. The case study is done through the observation of a survey conducted by the Institute of Economic Growth in 2017. The table below shows the data that became available as a result of the last survey conducted.

CDMO Office, Sonipat District (2017)

CDMO Office, Sonipat District (2017)

An analysis of the data portrays that even though the resources and infrastructure are adequate to the population of Sonipat, the facilities are lacking in human resources. The data shows that 6 posts for the Medical Officers (MO) were sanctioned, but only 3 were filled. Despite the high number of deliveries, there was no sanctioned post of a gynaecologist, which can probably be a reason behind the high number of maternal deaths in the area. It was also found that the Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) program was not functioning in the district for the past 2 years. O.P. Jindal University, which is in the heart of Sonipat, houses a total of 7482 individuals, and has an adequate number of facilities, with 5 in-house doctors and 10 nurses. It has an isolation facility ward for cases of communicable diseases. It has an ambulance and referral service to hospitals in the NCR. These facts show that there is an acute shortage of human resources for healthcare in the area. Even though an adequate number of posts were sanctioned, there was no qualified personnel to fill them, and there were no sanctions for important positions. The case of O.P. Jindal university shows that good healthcare requires good investment and incentive for the staff, which the Sonipat administration has failed to provide to the staff of healthcare centres owned by the state.

The arguments mentioned above portray the acute necessity of universal healthcare in India. The ideals of our constitution implore for the right to health to be established, which gives universal healthcare constitutional support. The failure of the 12th Five-year Plan showcases the failures that can happen if the framework for such a plan is not well-thought-out or well-invested. The example of Sonipat further portrays the need for increased investment in healthcare, which can be achieved by the utilization of universal healthcare. Although there is no concrete data available for the crisis which the nation recently endured, it can be concluded that the approach of universal healthcare could have allowed us to endure this crisis better, as there would have been lesser chances of shortage of supplies like oxygen because of the increased investment. The first step towards the policy of universal healthcare should be to strengthen existing institutions of insurance and learn from the mistakes in the implementation of the RSBY.

References

1.http://iegindia.org/upload/uploadfiles/Sonipat%20Haryana%202017.pdf

2.http://ijariie.com/AdminUploadPdf/RIGHT_TO_HEALTH__A_CONSTITUTIONAL_MANDATE_IN_INDIA_ijariie5596.pdf

4.http://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/files/Twelfth%20Five%20Year%20Plan%20Health%202012-17.pdf

Image Credit: www.financialexpress.com