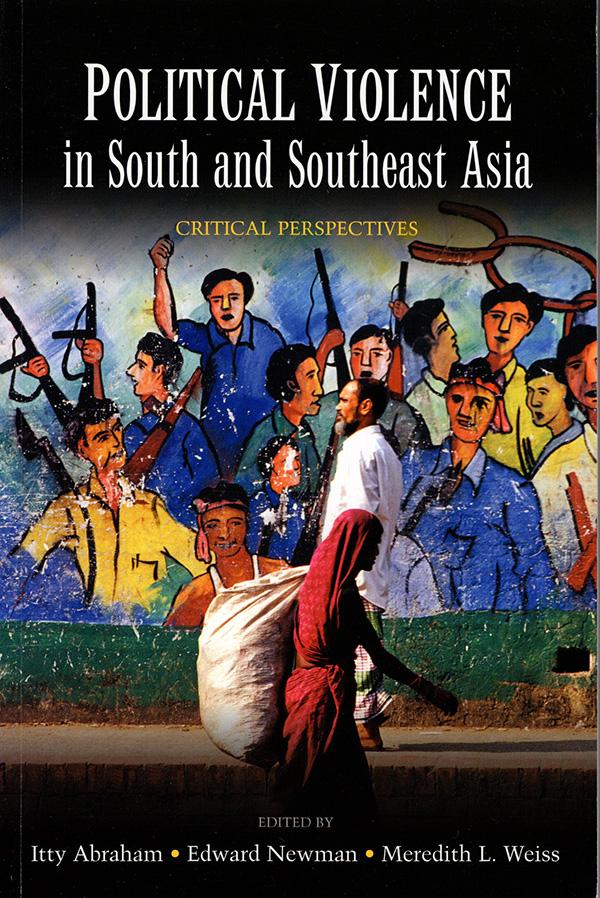

Political Violence in South and Southeast Asia: Critical Perspectives

Editor: Itty Abraham, Edward Newman, Meredith L. Weiss

Publisher: UNU Press, Tokyo, 2010. 224 Pages

Written against the framework of persistent threats to human security, ‘Political Violence in South and Southeast Asia: Critical Perspectives’ is a volume of extreme relevance and consequence. The book brings together numerous political scientists and anthropologists with in-depth knowledge of the socio-political environment of the two regions. It aims at understanding the interaction between violent and non-violent politics, and in doing so, it defines political violence as consequential and strategic, as opposed to spontaneous and senseless. Intending to shift the narrative of understanding violence solely from the standpoint of terrorism, the book develops a critical understanding of violence by dwelling on its social and structural context.

Divided into eight distinct chapters, the book takes cognizance of both state and non-state actors in a violent landscape. While concentrating on the local events of political violence in countries of South and Southeast Asia, the authors underline the significance of identities and the process of their consolidation, the character of states, geographic borders, external influences, and patterns of rebellion, in determining the manifestations of political violence.

Arguing that the theories of economic greed, grievance, regime type, and state collapse are guilty of facile claims and problematic conceptualization of political violence, the authors critique the narrow construction of the concept and the premature assumptions regarding its victims and perpetrators. In doing so, they focus on exploring the aims, approaches, consequences, and conceptual dimensions of such violence, without dwelling deep into the causes of the same. In analyzing the different brands of violence, the authors place their focus on assassinations, riots, pogroms, ethnic cleansing, and genocides in the two regions.

In his first chapter, Sankaran Krishna compares the assassinations of two political leaders in India – Mohandas Gandhi, and Rajiv Gandhi. The author presents a key argument underlining the changing moral economy of political killing in South Asia. Highlighting the context in which the two killings took place, Krishna argues that assassinations in the region have shifted from being carried out in the name of a larger cause or principle (Godse’s idea of saving India) to ‘a consequence of a blowback’ – which represented India’s choice of active participation in the Sri Lankan civil war, in the case of Rajiv Gandhi. Buttressing his argument, the author also takes into account the killings of Benazir Bhutto and Indira Gandhi. He does, however, present an uncomfortable and curious narrative by viewing these assassinations as attempts of suicide. Claiming that Gandhi’s insistence on fasting until death and refusal to be protected by the state, and Rajiv and Indira Gandhi’s deliberate lax in their security were rehearsals for eventual suicides, the author makes rather unsettling and complex arguments, one, defining Gandhi’s killing as a moral assassination, and two, by dwelling deep into the writings of Godse and portraying him as a man of rationality against the mainstream narrative of associating him solely with terrorism.

Later, presenting one of the central arguments of the book, Paul Brass, in his chapter on forms of collective and state violence in South Asia, argues against violence being defined as senseless. Asserting that all kinds of violence have their strategic purpose, he lays down the critical concept of an Institutionalised Riot System, arguing that riots are systematic and organised. Claiming that riot production consists of different stages, which are usually analogous to a staged production of drama, Brass states that the first stage is that of rehearsal, followed by enactment, and interpretation. While the rehearsal stage consists of those who arouse sentiments, consisting of politicians, ‘respectable’ group of university professors, and the lower ‘unrespectable’ groups of informants, local party workers, and journalists, the stage of enactment consists of false and inflammatory media reports. It brings together, on the one hand, university professors and students forming a part of the local crowd, and on the other hand, criminals recruited to burn, loot and kill. The final stage of interpretation and explanation is especially crucial to understanding the sustenance of such violence, which involves attempts at making the riot appear as spontaneous, as opposed to planned. What is witnessed is an active shift in responsibility to those who are not directly involved in riots, and even those who vehemently oppose the idea of rioting. The author substantiates his claims by associating the Riot System with examples from Northern India, particularly citing the killings in Meerut in 1982 and 1987.

The second half of the book is majorly devoted to a comparative approach to study mass violence and the impact of external influences in the region. The authors, in their respective chapters, provide detailed empirical evidence by dwelling deep into the case studies of different countries. Geoffrey Robinson, in his chapter, identifies three distinct ways in which the countries of Southeast Asia have witnessed violence. The states are either defined as principal perpetrators, as in the case of Indonesia in East Timor and the regime of Khmer Rouge in Cambodia; or as facilitating violence through propaganda and militia or inaction during mass violence, as with the case of Indonesia during the 1965-66 massacre. Finally, the state, according to Robinson, has also served as a vital link in the formation and spread of violent societal norms and modes of political action. He identifies the patterns and correlations between a level of violence and the character of states. An argument is made that because the military is designed to organize violence, any state where the military had an active role in the past has experienced more violence, as in the individual cases of Thailand, Philippines, Indonesia, or Burma. On the other hand, religious and ethnic violence, including riots, occurs almost always in newly democratizing states.

While Naureen Chowdhury Fink points out the contestations surrounding the borders of Bangladesh, Natasha Hamilton-Hart lays down the extent of external influences on political violence in Southeast Asia. She identifies the first wave of such influence, in the form of overt support to principal perpetrators, starting with the large-scale military support by China and the Soviet Union to the Vietnamese communists after the conflict escalated to open warfare involving American troops from 1964. Citing the United States military support and its deliberate silence during the massacre in Indonesia, the author identifies a direct link between the United States and the ongoing political violence in Indonesia. She also cites the US’ support to the Philippine government’s suppression of the rebellion, and to non-communist insurgent groups in Cambodia, and the Western support to Khmer Rouge – where lethal weapons from China, the US, and the UK flooded the country. In citing these examples, the author presents the extent to which external support has been instrumental in sustaining violence in the region. Later, external support is reported to have taken the form of training of police, militaries, insurgents, and other actors, along with a provision of intelligence and logistical support.

Vince Boudreau, in his chapter on recruitment and attack in Southeast Asian collective violence, argues that the patterns of collective violence in the region are influenced by trade-offs between efforts to recruit supporters and strike at adversaries. He also identifies a correlation between the nature of violence and the mode and strategies used for targeting the victims. A riot, for example, even when purposely produced by professionals – will likely be less discriminate than a coordinated attack by guerrillas; or a bomb detonated in a marketplace will likely be less discriminating than one thrown into a church. Identifying five such degrees of discrimination, Boudreau ranks them in an order of descending brutality – from indiscriminate attacks to indiscriminate categorical violence which employs a strategy designed to hit anyone who belongs to a particular socio-cultural category. Then comes to discriminate functional, referring to a strategy that targets individuals playing a particular occupational or political role, followed by the third strategy – discriminate personal, implying attacks on specific individuals based on something they have done, and lastly attacks on property.

Finally, towards the end of the book, an argument is made regarding the totalizing logic of sovereignty of the state, where the author takes into account different political movements and illustrates how these movements are perceived as subversive irrespective of their motive. The argument implies that the ideological movements because they embody a critique of the state, are much more difficult for the state to subsume without violence.

By adopting a comparative approach to study violence perpetrated by both, state and non-state actors, the book successfully underlines the conceptual similarities that exist within the societies, with regards to patterns and dimensions of violence. Because the book employs detailed contemporary evidence in explaining its critical concepts, it becomes a rather pertinent reading providing a wide scope for further analysis of similar events. Further, it successfully illustrates the correlations that exist between the character of states and the level and modes of violence, and in the reviewer’s opinion, can successfully go beyond the regions of South and Southeast Asia, to explain behavioural politics in more violent societies of West Asia and Africa.