Abstract

Following the Galwan valley clash in 2020, Ladakh has become the most important place of strategic and operational importance since it adjoins two adversarial neighbours who are strategically aligned with each other. China’s belligerence is taking many forms such as information warfare, land transgression, allegations of hacking, etc. The recent claim of unfurling of the Chinese flag supposedly in Galwan, which was later clarified to have been done in another location is a spoke of its information warfare against India. China’s construction activities enabling quick buildup of its troops and armaments are also a major cause of concern for India. While there are some initiatives launched by the Indian army and the Central government to strengthen the infrastructure in the Northern borders, special attention needs to be paid towards the holistic development of human resources and infrastructure in Ladakh.

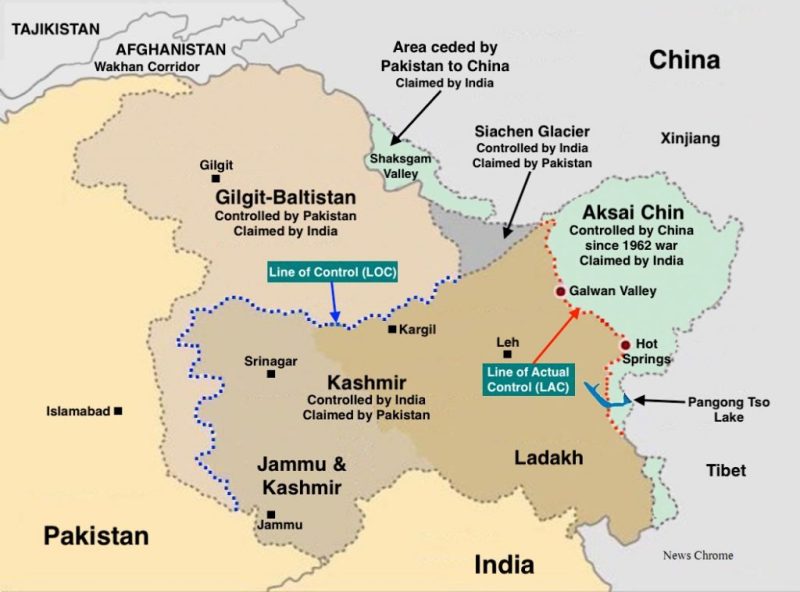

2022 began with a fresh show of Chinese belligerence in Ladakh, with a well-known Chinese media outlet putting out a tweet saying, “China’s national flag rises over Galwan Valley on the New Year Day of 2022“, following up with a short video of the event. The tweet further claimed that the flag was special, having flown earlier over Tiananmen Square in Beijing[i]. As Indian government sources confirmed that the ceremony did not occur in any disputed area, the Indian Army released photographs of soldiers hoisting the flag in the Galwan Valley on the occasion of the New Year[ii]. In other incidents across the rest of the Line of Actual Control (LAC), China suddenly ‘renamed’ 15 locations in Arunachal Pradesh, continuing efforts to undermine Indian sovereignty in that state. The Chinese embassy in Delhi wrote to counsel Indian MPs who had attended a reception hosted by the Tibetan government in exile in late December 2021[iii]. The frigid relationship between the two nations was underscored once again by the inconclusive outcome of the 14th round of Corps Commander’s talks held on the LAC on 12 Jan 2022[iv]

Chinese activities have not been restricted to the information domain alone. Construction of a bridge across the Pangong Tso, starting 20 km east of Finger 8 to connect its North and South banks, has come to light, providing an additional approach for a quick build-up of troops and logistics. While the above actions by China, both in the realm of information warfare and otherwise, have been effectively countered by the Indian government[v], the overall situation across the entire LAC continues to be of significant concern. This is despite the much-publicized sharing of sweets between Indian and Chinese troops at ten border crossings across the LAC[vi] in January.

Strategic Importance of Ladakh

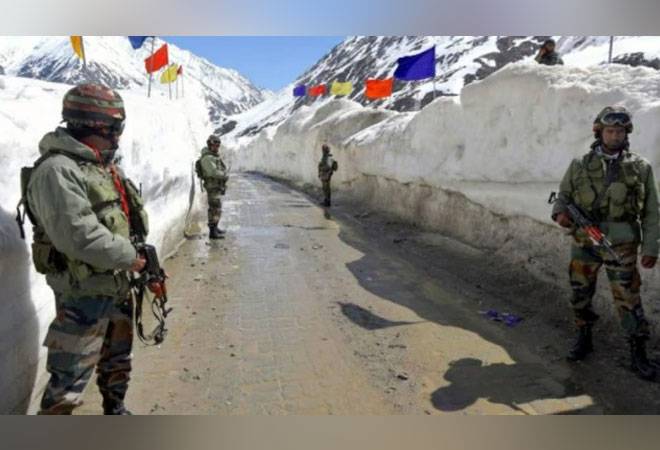

As compared to the rest of the LAC, the situation in Ladakh is serious. The killing of 20 Indian soldiers, including a Commanding Officer, in June 2020 has thrust the region into the nation’s collective consciousness. Galwan, Gogra, Daulet Beg Oldi, Pangong Tso, and Chushul are household names across the country and the public today is better educated about the sheer complexity of the border issue and our history of dealing with China on the matter. The importance of safeguarding national sovereignty has taken centre stage with issues such as the institution of ‘no patrolling zones’ and perceptions about the LAC being subjected to frequent debate in the media and elsewhere.

In the aftermath of the Galwan events, the strategic importance of Ladakh, seen more through the lens of tourism in tranquil times, has acquired renewed relevance. It is the only borderland of India adjoining two hostile states, both of which have gone to war with India at different times for their own reasons. Ladakh abuts Gilgit Baltistan, which is under illegal occupation of Pakistan, and Tibet, which is under China’s forced occupation. As the likelihood of collusive action between these countries increasingly grows, Ladakh will remain primus inter pares amongst all the regions on our Northern borders for strategic and operational reasons. Accordingly, plans to bring about a qualitative change in capacity and capability in all aspects of the region’s development to meet security challenges and human aspirations acquire greater importance vis-a-vis other locations.

The above aspect is well appreciated by the Central Government, which has taken many initiatives towards strengthening infrastructure development along the Northern borders in recent years. With regards to Ladakh, development has accelerated dramatically post creation of the Union Territory (UT) of Ladakh in 2019. A review of the UT Administrations’ activities after two years of its creation by the Lt Governor during a media interaction reveals the scale and scope of its achievements[vii]. Future plans are contained in a comprehensive ‘Vision Document,’ prepared on its behalf by a reputed consultancy, available on the internet[viii]. The Document is a comprehensive data-backed effort, listing the status of various developmental markers today and the desired end state. Achieving the vision would require effort, time, and planning for its translation into practical and prioritized implementables, after further considering risks, costs, benefits, and overall viability while adhering to timelines. Despite the progress made on many fronts and considering the constraints remaining, continued and focused long-term efforts by the administration are required here: equally important, the current and future security perspective has to be a key pillar of such plans.

Development Issues and Imperatives

A key priority that requires greater impetus is to accelerate the movement of locals for populating areas that, for reasons of geography and proven Chinese intent, have acquired strategic or operational significance. Page 9 of the Vision Document[ix] mentions that 65% of the total population is in and around Leh and Kargil cities. Though the paper has recommended setting up other population centres, enhanced hostile activity by China in and around places like Demchok on the LAC warrants that such areas also be included for consideration. In recent years, the Border Roads Organisation (BRO) has dramatically enhanced connectivity. Greater resources and manpower have constructed important roads and opened up East Ladakh and other parts of the UT[x]. The next step is to actualize a long-term plan with short and intermediate goals, which could see the setting up of small townships – after creating suitable infrastructure in housing, health, education, connectivity, and other civic amenities to support small-sized populations. Here the focus has to be on providing livelihood options other than the purely pastoral, with options explored for setting up Small Manufacturing Enterprises (SMEs), which might take time to prove financially viable. In this respect, China has succeeded with the construction of border villages and resettlement of Tibetans in areas opposite the LAC in Arunachal Pradesh and its disputed border with Bhutan[xi]. Though the Indian experiment in that region, which commenced post-1962, has not been as successful, it has to be pushed through in Ladakh. Here, reconciling developmental cum security needs with genuine environmental concerns would be necessary, considering that the Army’s premier firing range in Ladakh in the Tangtse Chushul area was closed some years ago for such reasons.

There is scope too for the military, as an essential stakeholder to assist in development in other spheres, such as preparation of dual-use facilities; helipads and Advanced Landing Grounds wherever feasible, are one example. Another option is to create infrastructure for specialized training in the Ladakh region – archives of the Press Trust of India mention an international training event, ‘Exercise Himalayan Warrior’ held in 2007 where Indian and British troops trained together in mountain warfare techniques in an area North of Leh[xii]. Training facilities of this nature would naturally benefit the local economy, though the fallout of such strategic signalling would have to be carefully weighed.

A fourth option to enhance the military’s participation, albeit indirectly, is to increase local recruitment. While recruit balancing would be carried out at Army Headquarters, there is a need to examine the feasibility of expanding the number of Ladakh Scout battalions (either regular units or on the Territorial Army model), which are eminently suited for fighting in such terrain. Being a permanent measure, this would offset, to an extent, the expense on induction of at least a few units from outside Ladakh. Benefits accruing from deploying local sons of the soil can be easily appreciated.

Harnessing through Civil-Military Engagement

At the turn of the century, it was in Ladakh that the Indian Army launched Operation SADHBHAVNA. Displaying strategic foresight, then GOC 14 Corps, Lt Gen Arjun Ray, set a one-point aim – ‘To Forestall Militancy in Ladakh.’ The program, a runaway success, was adopted subsequently by other field formations of the Indian Army. A process of continued oversight, course correction, innovation, and streamlining at various levels has made it an effective tool for helping assimilate our border populations into the national fold by winning hearts and minds. Here, it must be emphasized that SADBHAVNA has not been conceptualized as a developmental program per se. Neither is such an approach being followed on the ground – the projects being small, community-based, and including aspects of human resource development. It has had very positive spinoffs, with Ladakh being a significant beneficiary. With major development programs like the Ministry of Home Affairs’ flagship Border Areas Development Program (BADP) and others at the state level already in place, it is worth examining if an interaction between the local administration (at the panchayat level, say) and local military garrisons, both working from the ground upwards can help further synergize efforts to achieve optimum results.

Strategic contestation between India and China is a reality. The border issue will continue to influence many aspects of bilateral relations. Continued information warfare, a huge trade deficit, allegations of hacking, and now evidence of massive tax evasion by smartphone companies[xiii] are indicators of the need for a realistic appraisal of that country’s intentions and strengthening own capabilities. The development of Ladakh is an important factor in this regard.

Notes

[i] Free Press Journal, January 03, 2022.

[ii] ‘LAC Standoff: India exposes China’s lies in Ladakh as Indian Army hoists tricolour in Galwan Valley’. Ajeyo Basu, News24, January 04, 2022.

[iii] ‘China protests Indian MPs’ attending Tibetan reception, Tibet govt-in-exile fires back’. Geeta Mohan, India Today, January 01, 2022.

[iv] ‘Joint Press Release of the 14th round of India-China Corps Commander Level Meeting’. Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, January 13, 2022.

[v] ‘Government breaks silence, hits back at China on letter to MPs, Pangong bridge’. Shubhajit Roy, Indian Express, January 07, 2022.

[vi] ‘New Year: Indian, Chinese troops exchange sweets at Demchok and other border points’. Press Trust of India, January 01, 2022.

[vii] ‘Major transformation in developmental profile of Ladakh UT in nearly 2 years: Lt Governor’. Mohinder Verma, Daily Excelsior, September 18, 2021.

[viii] ‘Vision 2050 for UT of Ladakh’. Government of India.

[ix] ibid

[x] ‘Five Mega Road Infrastructure Projects Launched in Ladakh Amid Border Row With China’. PTI, October 01, 2021.

[xi] ‘More evidence of China building villages in disputed areas along borders with India, Bhutan’. Hindustan Times, November 18, 2021.

[xii] Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Ministry of Defence note, Exercise “Himalayan Warrior”. September 16, 2007.

[xiii] ‘Xiaomi India under lens: DRI says evasion of customs duty of Rs 653 cr by Chinese smartphone maker’. Economic Times, January 05, 2021.

Feature Image Credit: Bloomberquint

Map Credit: Newschrome

Images: www.deccanherald.com and www.business-standard.com