In 3 weeks since Russia’s president, Putin ordered on February 24 this year, a “special military operation” against Ukraine, many questions were asked on his reasons and goals.

Putin answered those questions in the early morning address to the nation on February 24. He referred to Russia’s particular concern and anxiety over the NATO expansion to the east and the US policy of containment of Russia through the military “settlement” of the Ukrainian territory. Transformation of Ukraine, historically a part of the Russian state, into an “anti-Russia” controlled and guided by the U.S. was nothing less, in Putin’s view than a real threat to Russia’s very existence.

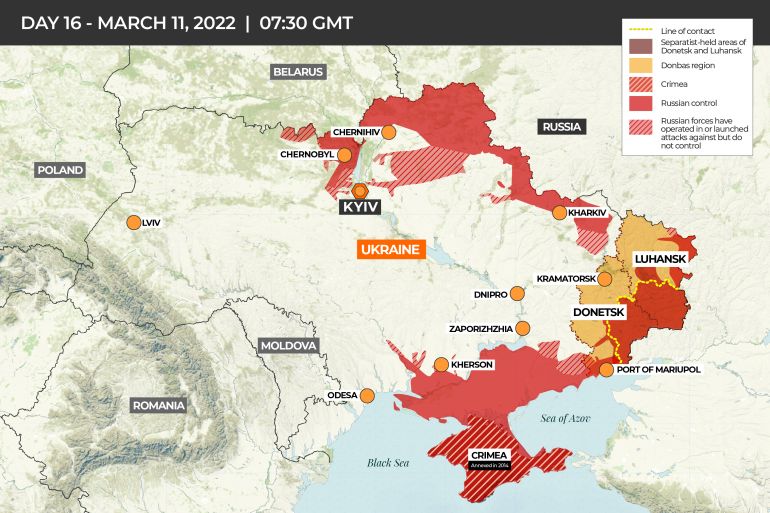

Putin went on to mention Ukraine’s use of armed forces against the pro-Russian separatists in Donbas, the potential threat that the Ukrainian nationalists could present for Russia-annexed Crimea, and Kyiv’s desire to acquire nuclear weapons. “Russia’s clash with these forces is inevitable.”

This was the start of Russia’s war on Ukraine. Few of us believed it would actually happen, but it did, nonetheless. Let’s start by trying to understand, why.

Russia’s red lines

According to John Mearsheimer, the West, and especially America, is principally responsible for the current crisis, which actually started at NATO’s Bucharest summit in April 2008, with the US pushing the alliance to announce a plan for Ukraine and Georgia’s prospective membership. Russian leaders characterized the move as an existential threat to Russia and promises to thwart it. Putin warned the West then and there: “if Ukraine joins NATO, it will do so without Crimea and the eastern regions. It will simply fall apart.”

Nobody listened, or paid attention, thus underscoring the second point from Putin’s pre-invasion speech: the West no longer treats Russia as a great power and will do whatever it deems necessary without taking heed of Russia’s legitimate interests. Instead, Ukraine was actively encouraged to expand its collaboration with NATO and crush the pro-Russian rebellion in Donbas by force. The U.S. and NATO supplied lethal weapons for Ukraine’s civil war, trained its armed forces and turned a blind eye to reports of atrocities that Kyiv and Kyiv-affiliated militias had committed in the region.

Ukraine started hosting joint land-based and naval exercises with NATO countries, effectively blocking Russia’s Black Sea fleet in its base in Sevastopol. In July 2021, Ukraine and America co-hosted a major naval exercise in the Black Sea region involving navies from 32 countries. In November 2021, the U.S. conducted its annual Global Thunder 22 exercises, which included strategic aviation practising nuclear strikes against Russia over the Black Sea and only 20 km from Russia’s borders. In parallel to that, Ukraine’s Deputy Minister of Defense announced his country’s aspirations to put as many US/NATO training centers in Ukraine as possible, which effectively amounted to a request for additional U.S. military personnel in the country.

As John Mearsheimer observed, Ukraine was fast becoming a de facto member of NATO. It wanted to use NATO’s rearmaments and the US political and strategic back-up to crush the separatist rebellion in Donbas and ensure “de-occupation and reintegration” of Crimea, now an integral part of the Russian Federation, by all necessary means, not excluding “military measures.” Russia’s fears of NATO’s ballistic missiles appearing on the Ukraine-Russia border, within 7-8 minutes of flying time to Moscow no longer seemed overly exaggerated. Putin described such a potentiality as NATO’s holding a knife to Russia’s throat and made an explicit connection between Ukraine’s aspirations of NATO membership and Kyiv’s plan to return Donbas and Crimea by force. Both were equally unacceptable.

Russia’s goals

According to the Russian leader, if Ukraine joined NATO, it would be tempted to implement its “de-occupation strategy” for Crimea through the use of force. NATO would then be obliged to help Ukraine under its Article V mutual defence clause. “This means that there will be a military confrontation between Russia and NATO,” Putin said. Such a war would soon turn nuclear. The Kremlin came to a conclusion that a pre-emptive strike on Ukraine was the only way to stave off a future Russia-NATO war over Crimea.

We haven’t seen it coming. It was hard to anticipate because Ukraine’s turning away from Russia and drawing closer to NATO did not start yesterday. Ukraine’s Yavoriv training ground hosted the first joint manoeuvres with NATO back in 1995. In 1997, Ukraine and NATO signed the Charter on a Distinctive Partnership. In 2000, the Ukrainian parliament ratified the Status of Forces Agreement, which enabled the stationing of NATO troops on Ukrainian soil. In 2002, Ukraine’s goal of eventual NATO membership was first voiced by its President; that goal has since become a part of the country’s official foreign policy doctrine. Ukraine’s forces took part in numerous NATO-led operations and missions over the years, from Bosnia to Kosovo to Afghanistan to Iraq. And Russia observed all of these developments over the period of near 20 years with calm and reserve, leaving an impression that Ukraine is free to proceed as it wants.

Moscow’s calm evaporated after Ukraine’s Maidan revolution of 2014 deposed Russia-leaning president Yanukovych and, through the revolutionary powers’ first acts, indicated a clear break with the last memories of the Russian influence. Symbolically, the very first move was to strip the Russian language of its semi-official status in the areas where significant numbers of Russian-speaking minorities lived. A clear indication was given as to the status of the Russian Black Sea Fleet naval base in Sevastopol – the new powers would prefer the Russian navy relocate to Russia proper at its earliest convenience. Plans were underway to offer these naval facilities to NATO.

Putin moved on to annex Crimea, which, in his view, was an act of strategic necessity. He apparently anticipated Ukraine’s eventually acquiescing to the fact.

It did not happen. Instead, Ukraine grew more nationalistic, and a significant number of its nationalists embraced anti-Russianism together with far-right politics and symbology. Hence, the Russian goals in the present war include “de-Nazification,” which must be read as Ukraine’s abandonment of anti-Russian nationalism and return to the quasi-Soviet ideology of “one people” with Russians and Belarusians. In other words, Russia would seek to reaffirm, if not impose, a version of the Ukrainian identity that was supported through both the imperial and the Soviet times — Ukrainians as a junior kinfolk to the Russian “older brother.”

The way out

With Ukraine’s capital Kyiv under assault and the southern port of Mariupol nearing utter destruction, calls for peace have intensified on all sides, including from Russia’s most important backers in China. Unfortunately, the search for a working compromise has not yet started in earnest. Ukraine’s original position at peace talks focused on the immediate withdrawal of all Russian troops from all of Ukraine, Crimea and Donbas included. From the Russian perspective, that would be equal to capitulation and surrender of a part of its own territory (Crimea), plus legal denunciation of a friendship and support treaty just concluded with Donbas.

Russia’s present terms for ending the war are equally unrealistic. They include Ukraine’s adoption of a neutral status and the abandonment of its hopes for NATO membership; acknowledgement of the Russian sovereignty over Crimea and the independence of separatist regions in the country’s east; and demilitarization. The objective of the regime change, disguised by the “de-Nazification” rhetoric, has not been voiced much as of recent.

Given the very fact of the ongoing war with Russia, the demand for demilitarization is clearly a non-starter. Russia’s insistence on Ukraine’s constitutional neutrality could, perhaps, be taken back to Ukraine’s parliament for a serious discussion; however, a ceasefire must be reached first for such a discussion to happen. As for Ukraine’s acknowledgement of Russia’s sovereignty over Crimea or independence of Donbas, these Russia-pushed items look more like the terms of surrender and cannot form the basis of a peace agreement.

A more plausible ground for a compromise could be the two states’ mutual pledge to refrain from all attempts to solve any outstanding issues by force in the future. That would stop short from Ukraine’s recognition of either Crimea or Donbas but would assure Russia that Ukraine has no plans to regain the lost territories by force. Russia would need to withdraw its army from all areas of Ukraine proper. Ukraine would have to accept that its fight for the return of Crimea and Donbas would now be restricted in its choice of means to mostly diplomatic and legal instruments. The assurances of a non-aligned, non-bloc status that Ukraine could give to Russia should be matched with Russia’s assurances of full compensation for the losses that this war inflicted on Ukraine’s economy and society. While such a compromise will most probably draw the rage of hawkish nationalists on both sides, it might actually form the foundation of a peace agreement that everyone needs.

Image Credits:

Feature Image: www.militarytimes.com

Putin Image: Al Jazeera

Map: Al Jazeera