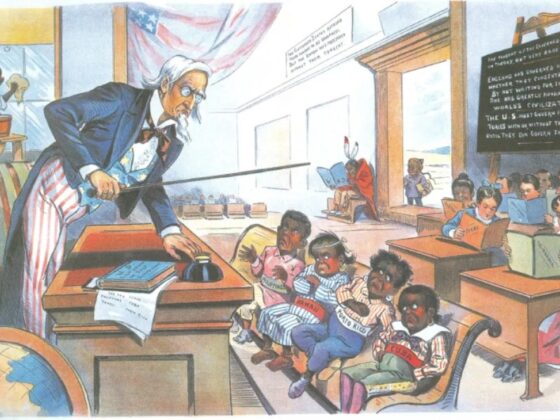

UK government ministers want the British Empire’s benefits taught in schools. Don’t let them ignore the death and destruction it inflicted says Professor Gurminder K Bhambra. Her observation is equally if not more important for India and other erstwhile colonies. Britain and other European colonial powers not only looted and decimated Indian economy over three centuries of colonial interaction but their ruthless exploitation led to much of the poverty that has afflicted the global south ever since. This fact of history must be taught extensively in Indian schools. There are many who propagate the fallacy that the British empire was beneficial but the truth that it was ruthlessly exploitative must be taught and researched in a big way. The wealth of the West was built on built on exploitation of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The West continues to dominate the global economic system and it is inherently exploitative. History teaching and research, from policy and science perspectives, are in dire need for elimination of Western bias.

Recent weeks have seen a variety of UK government ministers – fromOliver Dowden to Kemi Badenoch to, most recently, education secretary Nadhim Zahawi – both extol the benefits of British Empire and urge the teaching of those benefits. This follows on from the government’s response to the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, which set out the need for a new model curriculum for history which would advise schools on how best to teach these issues. This is all part of the government’s Inclusive Britain strategy which calls on us to acknowledge the rich and complex history of ‘global Britain’.

In the spirit of this call, I offer one account of the complex, entangled histories of colonial taxation and national welfare that continue to shape modern Britain. Few people know that colonial subjects from the Indian subcontinent paid taxation, including income tax, to the British government in Westminster. Or that that taxation was used to alleviate the conditions of poorer people within Britain at a time when the working class and middle class here were exempt from paying income tax.

Taxation – and the ways in which it is returned to citizens through welfare – is one of the main ways in which the ‘imagined community’ of the nation comes into being. That is, the relationship between taxes and welfare is part of the process of constructing institutions and the idea of the nation. If we were to recognise that this ‘imagined community’ was built not only through national taxes, but also colonial ones, then how might that change our understanding of what it is to be British today?

My grandfather, Mohan Singh, was born in 1913 in a small village in the Punjab, in what was then British India. He was four years old when his father, Gurdit Singh, died and 17 when his uncle, Harnam Singh, who had been supporting him, also passed away. My grandfather had planned on attending the Government College in Lahore, but – needing to support his mother and younger sister – he instead spent six months training as a boilermaker. He then got married to Pritam Kaur and travelled to Calcutta to work in a variety of factories, engineering works and rolling mills.

In 1942, he travelled to the British colony of Kenya – bringing his family over later – and worked for 18 years at the East African Railways and Harbour Company. He spent the last two decades of his life in the UK, working at Chalvey Engineering in Slough as a sheet metal worker before retiring at the age of 65 in Southall, west London.

Calls to ‘go home’ have been the refrain of right-wing opponents of immigration from at least the 1970s

Mohan Singh criss-crossed three continents during his lifetime, but he never left the jurisdiction of the British Empire. In his application for registration as a citizen of the UK and Colonies – in the aftermath of the British Nationality Act of 1948 – he wrote: “I was born in British India.” He further noted that he lived and worked in India and Kenya, two countries that were colonies of Britain. It was these connections that confirmed his citizenship and gave him the right to travel to and live in Britain. He duly exercised those rights but, on arrival, he had them called into question by the local population, who were either unaware of them or indifferent.

Calls to ‘go home’ have been the refrain of right-wing opponents of immigration from at least the 1970s – as well as having been plastered on the sides of vans as part of the UK government’s ‘hostile environment’policies of recent years. They are also implicit in an influential body of scholarly work oriented to questions of belonging and entitlement that argue for priority in public policy to be given to the ‘white working class.’ This is on the basis of them being ‘insiders’ who have contributed through their taxes to the wealth that is disbursed through welfare.

Former colonial subjects, like my grandfather, are regarded as immigrant outsiders even when they come to the metropole carrying passports of British citizenship. They are not seen to have contributed to the wealth of Britain by paying taxes and they are regarded as unfairly gaining access to the national patrimony. As Geoff Dench, Kate Gavron and Michael Youngwrite in ‘The new East End’: “As newcomers, their families cannot have put much into the system, so they should not be expecting yet to take so much out.”

Britain established direct rule over India after suppressing the 1857 Indian Mutiny (also known as the First War of Independence). In 1860, it implemented an income tax upon colonial subjects, in part to pay for the costs associated with those revolts. Initially, a 2% rate was imposed on those earning between 200 rupees and 500 rupees a year and a 4% rate on those earning above 500 rupees annually.

Famine Genocide 1876-1879 in British Raj Madras, India. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The arrival of the British in India – first via the English East India Company and then through direct rule – had brought endemic famine across the subcontinent

When my grandfather started work in the 1930s, the average wage for a skilled worker in British India was about 40 rupees a month. He was very unlikely to have paid income tax, however, as he would not have earned enough to meet the threshold, which by then was 2,000 rupees a year. Of the amount that was collected, around three-quarters went to the imperial treasury, with only one rupee in a hundred for local purposes. Local purposes included the building of canals and roads, but not the alleviation of poverty, not even in times of catastrophic famine.

The arrival of the British in India – first via the English East India Company and then through direct rule – had brought endemic famine across the subcontinent. The 50 years after the implementation of the income tax saw one of the most intense such periods of famine, in which it is estimated over 14 million people died of starvation. This was in the context of grain being exported by rail from the famine regions (including to Britain) and colonial taxes continuing to be collected even in the worst-affected areas.

In all cases, the demands of ‘sound finance’ trumped those of public health and the primary thing to be avoided was any idea that the poor in India should be maintained at public expense. Ensuring sufficient funds for the ensuing military campaign in Afghanistan – from the taxes paid by colonial subjects for local purposes – was of more importance than using those taxes to alleviate severe hunger and avert the deaths of millions.

Here, we see quite clearly that the idea of the ‘imagined community’ created through taxation and its redistribution did not include colonial subjects. The taxes that Indians paid to the imperial treasury and to local provinces did not give them any entitlement to the redistribution of that income. Worse, any relief provided during famines was often dependent on undertaking hard labour in camps at a distance from a claimant’s locality.

The most extreme instance was where the rations provided in return for heavy labour were scarcely above the level required for basic subsistence. The ‘Temple wage’ – named after the lieutenant-governor, Richard Temple, who brought it in – produced lethal results and, as Mike Davis notes in ‘Late Victorian Holocausts’, turned the work camps into extermination camps.

The death and destruction brought about by the Empire were known at the time. In 1925, Harry Pollitt, the leader of the Boilermakers Union in the UK, stated that the British Empire was drenched in blood. This was in the context of debates at the Trades Union Congress in Scarborough, where a resolution was eventually adopted – by three million votes to 79,000 – against imperialism and in support of the right of self-determination of those who were colonised.

Such sentiments, however, came up against more hard-nosed understandings concerning the utility of the Empire to those in Britain. As Labour foreign secretary Ernest Bevin proclaimed in Parliament in 1946, “I am not prepared to sacrifice the British Empire, because I know that if the British Empire fell … it would mean that the standard of life of our constituents would fall considerably.”

Here, Bevin acknowledged that the life of all within Britain was enhanced as a consequence of Empire. However, Empire was overwhelmingly disastrous for the majority of people subject to it. Their standard of life fell considerably as a consequence of colonialism and the famines it produced and, in many, many cases, they lost their lives to it.

One mode of survival was to move. This is why my grandfather moved from a village in the Punjab to train as a boilermaker in Lahore, before working in Calcutta, Nairobi and London. This is likely why his grandfather before him moved from famine-struck Orissa to Rajasthan to Punjab. These movements tend not to be seen to be part of the histories of Britain, global or otherwise, or of any consequence to understanding Britain or Britishness in the present.

The forgetting of the Empire involves also the forgetting of the political community – colonial and postcolonial – that was constructed through taxation. Few in Britain today understand the extent to which national projects – from social welfare to cultural institutions such as country houses, museums, and galleries – have been enabled through the taxes paid by former colonial subjects. There is an urgent need for us to recognise our shared histories and account for them.

One aspect of the ‘culture wars’ is the call to take the views of taxpayers into account when discussing ‘contested histories’. Samir Shah, the chair of London’s Museum of the Home, for example, argued that as heritage bodies are funded by taxpayers’ money, then the views of taxpayers – those he considers the silent majority – ought to be taken more explicitly into account. Given that both colonial subjects and their descendants paid taxes to the government in Westminster, then they/we also have a legitimate stake, in the government’s own terms, in how our shared history is represented. There is a benefit to the teaching of British Empire, but the reality is different from what these ministers suppose.

This essay was published earlier in openDemocracy and is republished under Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial 4.0 International License.

Feature Image Credit: The Irish Times

1 comment