Introduction

‘The Namesake’ by Jhumpa Lahiri (2003) and ‘A Fine Balance’ by Rohinton Mistry (1995) are accounts of fiction written during the millennial period. From a sociological perspective, both authors give us an insight into how human attitudes are moulded. The novels are based on Indian society and consider the influence of culture and traditions on human nature, which is testimony to how the plot progresses.

An outline of the plots

‘Namesake’ is a debut novel by the author Jhumpa Lahiri, and revolves around an Indian family settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America. The story begins with an introduction to the life of a pregnant woman, the mother of the protagonist, Ashima Ganguli in her twenties, struggling to find the ‘Bhelpuri’ she craves. The entire plot revolves around Ashoke and Ashima’s son, Gogol named after Ashoke’s favourite author Nikolai Gogol and his struggle to overcome the identity crisis and the shame he associates with the name. As the characters traverse through their lives, the reader witnesses Gogol moving to a new city for college, him changing his name to Nikhil, Ashoke’s death and Ashima’s loneliness. There are other supporting characters including Gogol’s sister Sonia, of which the most important are Maxine and Moushumi, who are the love interests of Gogol.

‘A Fine Balance’ is written by a non-resident Indian Rohinton Mistry who portrays how the lives of four different people: Dina Shroff who becomes Dina Dalal post her marriage; Ishvar and Omprakash Darji, and Maneck Kohlah, from different backgrounds, get associated with each other during the period of emergency (1973). It is set in an ‘unidentified’ city and is often considered Mistry’s critique of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her rule. He also gives the readers an account of their lives before Article-356 of the Indian Constitution was enforced. Dina is a Parsee survivor of child sexual abuse and becomes a young widow when she loses her beloved husband to an unfortunate accident. She is portrayed as a woman of solid resolve who tries to be financially independent and refuses help from her brother Nusswan Shroff. Ishvar and Omprakash are an uncle-nephew duo from the Chamar caste (Dalits) and therefore were involved with the caste-based occupation of leather tanning. This duo moves to the city in search of a respectable livelihood and plans to use their tailoring skill. Maneck is a pampered college student who is the son of a friend of Dina’s. Ishvar and Om become tailors for Dina who has taken up a contract from the garment industry and Maneck after a traumatising incident in the college hostel, shifts to Dina’s house as a paying guest. Dina often is taunted by her landlord, who is against any other activity being practised in his house, but she finds ways to elude him.

Emerging Themes – An Overview

| THE NAMESAKE | A FINE BALANCE |

| Ideal Indian Woman

Jhumpa Lahiri, through the character of Ashima Ganguli, brings out an ideal Indian woman. She is portrayed as a pious, devoted wife and a caring mother, who wears a saree, speaks broken English and sticks to her Indian culture and traditions. The author tells us that “She hates coming back to an empty house” when her husband and children move to various places for their work. This prompts her to take up a job at the local library, showing that women get used to the idea of domestic labour as love. Till the death of Ashoke, she looks after his needs and remains a ‘good’ wife. |

Women and Family Abuse

After her father’s death, Dina Shroff’s brother takes up the role of the head of the family, as is the norm. She is then brutally abused and beaten by her brother Nusswan to ‘correct’ her wayward behaviour. The brutality reaches an extreme point when she goes against his order not to get a haircut. He slaps her, asks Dina to take a bath before him, and looks on lecherously while she does. The author leaves no stone unturned to explain Dina’s brother’s arrogant and lecherous nature. |

| Benevolent misogyny

Ashoke Ganguli is a learned man who is the patriarch of the family. Though he is a man of few words, his actions prove masculine traits such as rationality and intelligence. This is in stark contrast to Ashima’s character, portrayed as emotional. Even though he is learned he believes that housework is a feminine activity and does not once help Ashima in her work. Even if he had wanted to, she would not let him because a ‘good’ woman fulfils her husband’s wishes and not vice versa. The author attempts to give the readers an overview of the concept of feminine duties and the burden on an Indian woman to uphold family integrity by slaving to the needs of the patriarch. |

The societal notion of the single woman

Indian society has marred the lives of its women in the name of culture and tradition. Dina as a widowed single woman lives with the constant fear of being questioned by people. Her aim for financial independence is testimony to the fact that she wants to establish for herself a ‘respectable’ position in the community. When she brings in Ishvar and Om to work for her, she is at loggerheads with herself and gives in to the decision because of her dire need for money. This shows that a single woman has to consider several factors and not just her aspiration to be valued in society. A heterosexual woman in a marital relationship with a heterosexual man equals perfection according to Indian norms. |

| Woman and Fidelity

Ashima and Moushumi can be compared in this regard because Ashima is portrayed as a loyal wife who is naive and has an eye for no man other than her husband while Moushumi, wife of Nikhil aka Gogol is a modern, well-read, PhD scholar who has a different take on sexuality and relationships. Moushumi has an extra-marital affair with another man which forces Gogol to leave the marriage. This shows that a woman exploring her sexuality is considered infidel and disloyal. |

Caste atrocities

The author vehemently tries to engage the readers with the concept of purity and pollution throughout the text. Ishvar and Om are from the Chamar caste whose lives in the village are described in detail. There is a specific instance of Ishvar’s mom being sexually exploited for trying to sneak mangoes from a landlord’s orchard to ameliorate her son’s hunger. The landlord uses this to exact sexual favours from her. Many such instances throughout the book exist with Ishvar being forcefully sterilised during the emergency due to his lower caste origins. With a picturesque description of these events, Mistry centres his conversation around caste-based atrocities rampant in the Indian society. |

Perception of women – A comparison

The portrayal of women in both books is strikingly different owing to the lens through which they are viewed. A commonality is that both authors are descriptive in their narratives with a focus on providing the readers with a vivid reflection of their thoughts and the situation in question. Despite this, there is a visible contrast in the writing method with Jhumpa Lahiri taking a platonic tone with the specificity of minute details, whereas Mistry uses strong writing to describe the despicable traditions and norms in the Indian society; also, evidence of a non-resident Indian’s view of the societal norms. Women characters in both novels are depicted with varying densities, touching upon the aspects of femininity conditioned by the patriarchal society.

Namesake

The fact that ‘Namesake’ is written by a woman does not make the patriarchal norms that are inherent in an Indian woman fade away. However, Lahiri’s portrayal of Ashima is brilliant in execution and gives life to the internal conflict that occurs in a woman, who has been sent away from her natal home to a foreign land thereby making the readers feel the pain of loneliness.

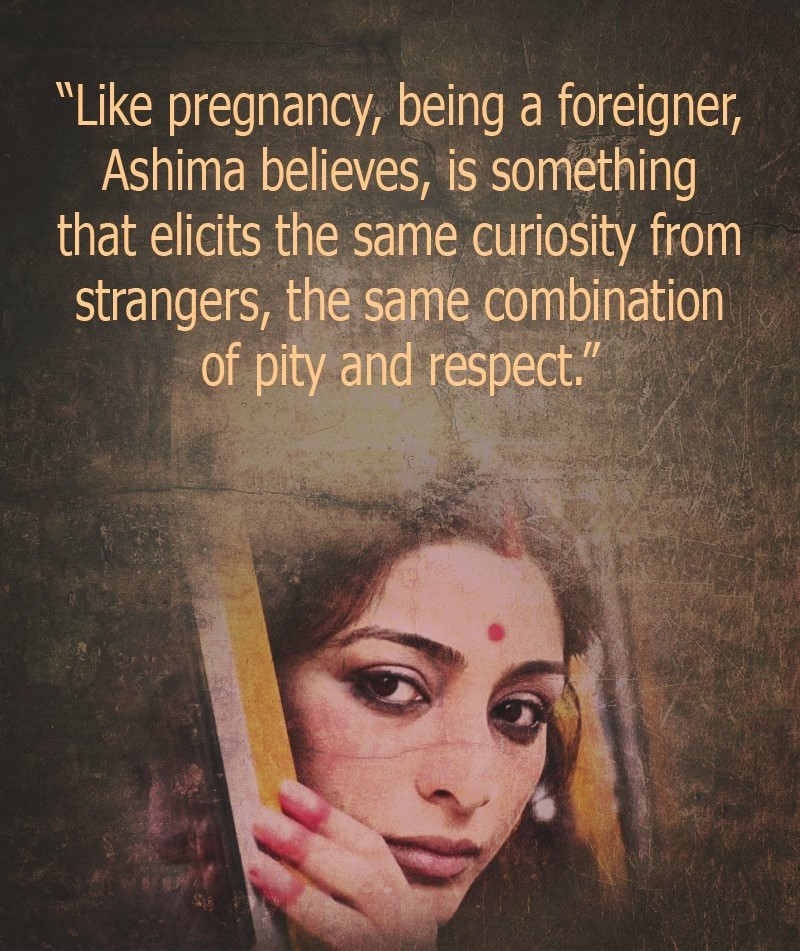

Ashoke is the only earning member of the family, her needs during pregnancy are also side-lined because Ashima knows that her husband “has to work”.

This quote in the image is from the book that elicits the idea that she, as a foreigner, was left feeling sad and lonely. Lahiri captures these nuances from a gendered lens, i.e., the suffering of every Indian woman who is married and has to stay away from their natal home. However, the portrayal of Ashima as a typical Indian homemaker and her lack of financial independence in the initial stages of the plot to one of financial freedom when she takes up a job at the local library can be likened to the Western concept of liberation. Ashoke’s death is also an event which brings out the strength in Ashima, despite feeling lost she moves on with a “life must go on” attitude.

Another character which has to be analysed from a feminist perspective is Moushumi, Gogol’s wife whom he later divorces owing to her infidelity. Lahiri’s writing, despite having the perks of the feminist notion of women, sticks to the idea of liberal feminism where the dichotomy of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ woman arises. Moushumi’s extra-marital affair is construed as a deviant from the dichotomous norm and this can be seen as an attempt to appease the larger group of the society. Taking into account Foucault’s work on sexuality, this deviance is constructed as bad behaviour. The fact that not everything is black and white and that there are shades of grey is forgotten in the portrayal of Moushumi, who is an educated, well-read doctorate scholar. Lahiri’s writing is therefore poetic in all its sense but the women characters in her book may come across as lacking depth due to its affinity to a single view of ‘liberated women’, despite the scope it had for exploring the roles of women.

A Fine Balance

The women characters in this book are few, and some of them are Dina Shroff, her mother and her sister-in-law. There is also a take on the atrocities of the caste system on women, which can be considered as taking Crenshaw’s intersectionalities into account. However, the entire book is all over the place due to its attempt to explore multifarious issues. Primarily of import are the character of Dina and her attempt at exploring her sexuality. The choice of words to describe an event like sexual abuse is sexualised rather than creating a wave of anger in the reader. Casual sexism can be seen throughout the book, probably reflecting the author’s desperate attempt to capture the reader’s interest. For example, a male gaze in explaining how Dina was shunned by her brother Nusswan for getting a haircut can come across as strong writing but can also find itself on the spectrum of voyeurism. He writes,

“She was standing naked on the tiles now, but he did not leave. “I need hot water,” she said. He stepped back and flung a mugful of cold water at her from the bucket. Shivering, she stared defiantly at him, her nipples stiffening. He pinched one, hard, and she flinched. “Look at you with your little breasts starting to grow. You think you are a woman already. I should cut them right off, along with your wicked tongue.”

Although these depictions may be to ensure that the reader understands the depth of patriarchy, they can also create in the minds of the readers a voyeuristic portrayal of child abuse. Though Dina is shown as a woman trying to propel her life and create her own destiny, it can be a shadow representation of women. The importance of Dina to the plot is minimised to abuse and being a widow struggling for financial freedom with no evidence of trauma outcomes, i.e. of her sexual abuse as a child, whatsoever. Though it has Dina as one of the main characters, the storyline seems like an attempt at a comprehensive and extensive description of the issues in the Indian society and soon the focus is lost. In comparison, we can say that the depiction of women in ‘Namesake’ is more poetic and has considerate sexism, whereas ‘A Fine Balance’ is profane in depicting women as fragile beings.

Conclusion

Thus, the portrayal of women in these writings derails from the feminist attitude of empathising with fellow women and showcases outright sexism both in the physical and social sense. An attempt from both authors could have been made to focus on the internal conflict that occurs in a woman with regard to exploring her sexuality. The works find value, in assuaging the larger societal constructs of monogamy in the case of Lahiri and trying to cover all issues plaguing the Indian society at one time in the case of Mistry. There is an essence of a condescending tone which is similar in both works. The works were of the millennial period, and therefore, it is also necessary to consider historical perception, but even this argument does not hold water because it was also the era of a feminist fictional writer like Arundhati Roy. Therefore, the women in both these works could have had better portrayals if an effort was taken in the right direction to understand gender politics of sexuality, power, and violence.

References

- C. A. M., & Lourdusamy, A. (2022). Review of Displacement, Space, and Identity in the Postcolonial Novels of Jhumpa Lahiri, Rohinton Mistry and Manju Kapur. International Journal of Management, Technology, and Social Science, 354–372. https://doi.org/10.47992/ijmts.2581.6012.0195

- (2023). Namesake (03) by Lahiri, Jhumpa [Paperback (2006)]. Mariner s, Paperback(2006).

- Mistry, R. (2023). A Fine Balance by Mistry, Rohinton [Vintage,2001] (Paperback). Vintage,2001.

- Alfonso-Forero, A. M. (2007). Immigrant Motherhood and Transnationality in Jhumpa Lahiri’s Fiction. Literature Compass. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4113.2007.00431.x

- Doron, A., & Raja, I. (2015). The cultural politics of shit: class, gender and public space in India. Postcolonial Studies, 18(2), 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2015.1065714

Featured Image Credits: German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ)