The nuclear tests, of May 1998, by India and Pakistan, marked an epochal juncture for South Asia. The Doomsday Clock maintained by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, jumped from 11:43 to 11:51, or just “9 minutes to midnight.”

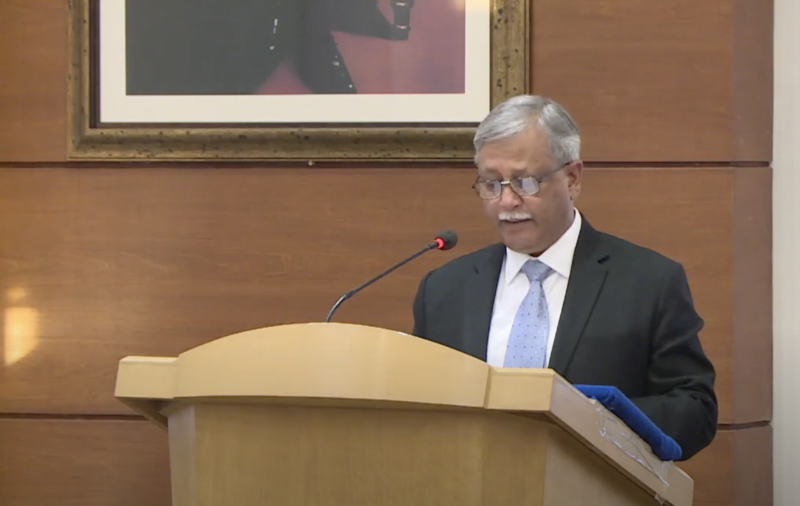

While, in India, the “Shakti” tests, do find celebratory mention, Pakistan observes the Chagai series of nuclear tests, as a national day, termed “Yom-e-Taqbir.” On the 25th anniversary of this event, Lt Gen Khalid Kidwai (Retd), currently, advisor, to Pakistan’s National Command Authority (NCA), delivered an address at the Arms Control and Disarmament Centre of the Institute of Strategic Studies, Islamabad.

Kidwai, who served, for 14 years, as the Director-General of Pakistan’s Strategic Plans Division (SPD), was at the heart of Pakistan’s NCA, and oversaw the operationalisation of its nuclear deterrent. Although his talk was for public consumption, given the historic absence of an Indo-Pak nuclear dialogue, some of Kidwai’s statements – if taken at face value – contain worrisome undertones, which need analysis.

After mentioning the rationale for Pakistan embarking on nuclear weaponization (“humiliation of the 1971 War followed by India’s nuclear test of May 1974”) Kidwai proceeded to enlighten the audience about the implications of Pakistan’s new policy of Full Spectrum Deterrence (FSD) and how it kept, “India’s aggressive designs, including the Indian military’s Cold Start Doctrine, in check.”

While retaining the fig leaf of Credible Minimum Deterrence (CMD), Kidwai went on to mention the “horizontal dimension” of Pakistan’s nuclear inventory, held by the individual Strategic Force Commands of the Army, Navy and Air Force. The “vertical dimension,” of the Pak deterrent, he said, encapsulated “adequate range coverage from zero meters to 2750 km, as well as nuclear weapons of destructive yields at three tiers: strategic, operational and tactical.”

While the missile range of 2750 km, corresponds, roughly, to the distance from a launch-point in south-east Sindh, to the Andaman Islands, and indicates the “India-specificity” of the Shaheen III missile, it is the mention of “zero metres” that is intriguing. Pakistan already has the 60 km range, “Nasr” missile, projected as a response to India’s Cold Start doctrine. Therefore, unless used as a colloquialism, Kidwai’s mention of “zero metres” range could only imply a pursuit of ultra short-range, tactical nuclear weapons (TNW), like artillery shells, land mines, and short-range missiles, armed with small warheads, of yields between 0.1 to 1 kiloton (equivalent of 100 to 1000 tons of TNT).

By shifting from CMD to FSD, with the threat of nuclear first use, to defend against an Indian conventional military thrust, Pakistan is aping the, discredited, US-NATO Cold War concept of Flexible Response. Fearing their inability to withstand a massive Warsaw Pact armoured offensive, this 1967 doctrine saw the US and NATO allies deploy a large number of TNW to units in the field.

However, the dangers of escalation arising from the use of TNW were soon highlighted, by US Secretary Defence, Robert McNamara’s, public confession: “It is not clear how theater nuclear war could actually be executed without incurring a very serious risk of escalating to general nuclear war.” This marked a turning point in US-NATO nuclear strategy.

Kidwai’s speech contains three statements of note. Firstly, he attempts to dilute India’s declared policy of “massive retaliation” (MR), in response to a nuclear strike, by claiming that Pakistan possesses an entire range of survivable nuclear warheads of desired yield, in adequate numbers, to respond to India’s MR. He adds, “Pakistan’s counter-massive retaliation can therefore be as severe (as India’s) if not more.”

Far more significant is Kidwai’s declaration that, since Pakistan’s missiles can threaten the full extent of the Indian landmass and island territories, “…there is no place for India’s strategic weapons to hide” (emphasis added).

Secondly, in an attempt to downplay India’s (inchoate) ballistic missile defence (BMD), he declares that in a “target-rich India”, Pakistan is at liberty to expand the envelope and choose from counter-value, counterforce and battlefield targets, “notwithstanding the indigenous Indian BMD or the Russian S-400” (air-defence systems).

Far more significant is Kidwai’s declaration that, since Pakistan’s missiles can threaten the full extent of the Indian landmass and island territories, “…there is no place for India’s strategic weapons to hide” (emphasis added). The assumption, so far, was that, given its limitations in terms of missile accuracy, real-time surveillance and targeting information, Pakistan would follow a “counter-value” or “counter-city” targeting strategy. The specific targeting of India’s nuclear arsenal, especially, if undertaken by conventional (non-nuclear) missiles, would add a new dimension to the India-Pakistan nuclear conundrum.

Delivered in the midst of Pakistan’s acute financial crisis, as well as the ongoing political turmoil and civil-military tensions, one may be tempted to dismiss Lt Gen Kidwai’s recent discourse. However, as the longest-serving, former head of the SPD and architect of Pakistan’s nuclear deterrent, his views are widely heard and deserve our attention.

Having voluntarily pledged “no first use” (NFU), India’s 2003 Nuclear Doctrine, espoused a “credible minimum deterrent” and promised “massive retaliation,” in response to a nuclear first strike. Since then, our two adversaries, China and Pakistan, have expanded and upgraded their nuclear arsenals, presumably, with corresponding updating of doctrines. India’s strategic enclave has, however, not only maintained a stoic silence and doctrinal status quo but also defended the latter.

BJP’s 2014 Election Manifesto, had undertaken to “revise and update” India’s nuclear doctrine and to “make it relevant to current times,” but this promise has not been kept. Thus, India, currently, faces a moral dilemma as well as a question of “proportionality”: will the loss of a few tanks or soldiers to a Pakistani nuclear artillery salvo, on its own soil, prompt India to destroy a Pakistani city of a few million souls? Since India, too, has developed a family of tactical missiles, capable of counterforce strikes, does it indicate a shift away from CMD and NFU, calling for a response from our adversaries?

These are just some of the manifold reasons why there is a most urgent need for the initiation of a sustained nuclear dialogue between India and Pakistan, insulated from the vagaries of politics. Such an interaction, by reducing mutual suspicion and enhancing transparency, might slow down the nuclear arms race and mindless build-up of arsenals.

This article was published earlier in Indian Express.