At the beginning of his famous first chapter, Clausewitz defines war as mentioned above within a hierarchy of purpose, aims, and means. His renowned formula is related to this definition. At the end of the same chapter, nevertheless, he introduces the consequences for the theory of war from this initial reasoning about the nature of war and states: “Our task, therefore, is to develop a theory that maintains a balance between these three tendencies, like an object suspended between three magnets”

Strategy Bridge

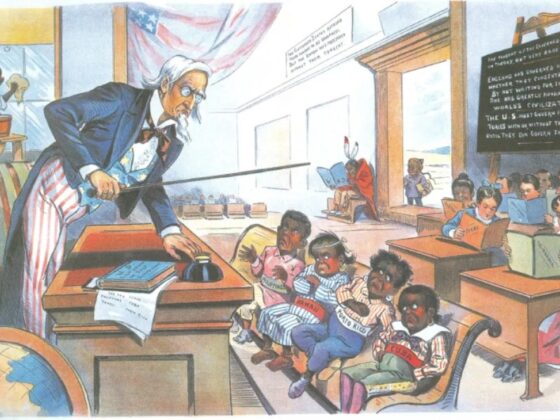

“The Strategy Bridge concept leads to battle-centric warfare and the primacy of tactics over strategy.”

At the outset, I would like to emphasise that in war and in violent action, justifiable ends do not legitimate all means. But I won’t solely treat the means applied by Hamas on October 7th, nor that of the Israel defence forces afterwards. Nevertheless, if someone argued that the ends justify all means, this would have to be applied to both sides. I want to highlight more principal arguments concerning the ‘end-aims-means’ relationship by contrasting a mere hierarchical approach, which is, in my view, leading to a reversal of ends and means, and a floating balance of them. The task of coming to a proper appreciation of Clausewitz’s thoughts on strategy is actually to combine a hierarchical structure with that of a floating balance. This article examines the relation of purpose, aims and means in Clausewitz’s theory and highlights that this relation is methodologically comparable to the floating balance of Clausewitz’s trinity. Modern strategic thinking is characterised by the end, way (aim), means relationship and the concept of the ‘way’ as the shortest possible connection between ends and means (consider, for instance, Colin Gray’s concept of a strategy bridge[1]). This notion stems from a very early text of Clausewitz: ‘As a result each war is raised as an independent whole, whose entity lies in the last purpose whose diversity lies in the available means, and whose art therein exists, to connect both through a range of secondary and associated actions in the shortest way.’

Nevertheless, here we can detect the fundamental difference in many of Clausewitz’s interpretations, which understand strategy as the shortest way of connecting purpose and means (battle and combat). Within this quote, Clausewitz speaks of war as an independent whole, a notion which he later rejects fervently. A central distinction is the concept to which the means attaches: the Taoist tradition and Sun Tzu hold that the means connects directly to the political purpose of the war; in contrast, for Clausewitz, the means attaches to an intermediary aim within a war, which must be sequentially achieved prior to the fulfilment of the war’s political purpose. The distinctive feature of the Taoist tradition is that strategy as a “way” effectively becomes tactics, in the sense that there exists no “strategic” aim, in the meaning of an intermediate military “strategic” war aim inserted between the political purpose of the war and tactical combat.

Battle-centric Warfare: Winning battles and losing the War

If strategy is nothing else than the direct way of linking the political purpose with the means, understood as combat, this understanding results in a ‘battle-centric’ concept of warfare that privileges tactical outcomes. One might attribute the loss of the Vietnam War, as well as the defeat of the US in Afghanistan and Iraq, to this misunderstanding about battle. In the early 1980s, Colonel Harry G. Summers Jr wrote a most influential work about the faults made in the Vietnam War. He observed that the US Army won every battle in Vietnam but finally lost the war. Summers recounts an exchange between himself and a former North Vietnamese Army officer some years after the war. It went something like this: Summers: ‘You never defeated us in the field.’ NVA Officer: ‘That is true. It is also irrelevant.’ [2]Winning battles does not necessarily lead to winning the war, and not only in this case. The same point can be made about Napoleon’s campaign in Russia. Napoleon won all the battles against the Russian army but lost the campaign. It was precisely this observation that led Clausewitz to denounce battle-centric warfare.

‘War is thus an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will,’ Clausewitz wrote at the beginning of his famous first chapter of On War (75).[3] ‘Force … is thus the means of war; to impose our will on the enemy is its purpose’, he continued. ‘To secure that purpose, we must make the enemy defenceless, which, in theory, is the true aim of warfare. That aim takes the place of the purpose, discarding it as something not actually part of war’ (75). This seemingly simple sentence reveals the core problem: what does it mean that the aim ‘takes the place’ (in German: vertritt) of the purpose? Are they identical or different? To put it bluntly, At the beginning of his famous first chapter, Clausewitz defines war as mentioned above within a hierarchy of purpose, aims, and means. His renowned formula is related to this definition. At the end of the same chapter, nevertheless, he introduces the consequences for the theory of war from this initial reasoning about the nature of war and states: “Our task, therefore, is to develop a theory that maintains a balance between these three tendencies, like an object suspended between three magnets” (89).[4] In relation to the concept of strategy, we must combine a hierarchical understanding of the purpose-aims-means-rationality with that of a floating balance of all three.

Presenting any of these elements as an absolute would be artificially to delimit the analysis of war, as the components are interdependent. Clausewitz’s solution is the ‘trinity’, in which he defined war by different, even opposing, tendencies, each with its own rules. Nevertheless, since war is ‘put together’ in this concept of three tendencies, it is necessary to consider how these tendencies interact and conflict simultaneously rather than one being absolute. Clearly, if we go to war, there is a purpose for that war, and different purposes for war are possible. Each of these possible purposes is connected with different achievable military aims, and finally, each aim can be achieved by various means. The question, therefore, is whether all three are incorporated into a hierarchy or whether their relationship must be understood as a floating balance among them.

Purpose, Aims, and Means in War

Clausewitz explains this dynamic relationship of purpose, aims and means in war in Chapter Two of Book One. At the beginning of Book One, Chapter Two, Clausewitz writes that ‘if for a start we inquire into the [aim] of any particular war, which must guide military action if the political purpose is to be properly served, we find that the [aim] of any war can vary just as much as its political purpose and its actual circumstances’ (90). The consequence of this proposition is that not every aim and means serves a given purpose. The problem of the relationship between purpose and aims is that each element of the purpose-aims-means construct has a rationality of its own, which Clausewitz emphasises in his proposition that war has its own grammar, although not its own logic. He writes, for example, ‘we can now see that in war many roads lead to success, and that they do not all involve the opponent’s outright defeat.’ Clausewitz then summarises that there exists a wide range of possible ways (94) to reach the aim of war and that it would be a mistake to think of these shortcuts as rare exceptions (94). For example, Clausewitz wrote: ‘It is possible to increase the likelihood of success without defeating the enemy’s forces. I refer to operations that have direct political repercussions, that are designed in the first place to disrupt the opposing alliance’ (emphasis in the original) (92).[5]Another prominent example, Clausewitz emphasised, was the warfare of Frederick the Great. He would never have been able to defeat Austria in the Seven Years’ War if his aim had been the outright defeat of Austria. Clausewitz concludes if he had tried to fight in this manner, ‘he would unfailingly have been destroyed himself.’ (94). After explaining other strategies besides the destruction of the enemy armed forces, he concludes that all we need to do for the moment is to admit the general possibility of their existence, the likelihood of deviating from the basic concept of war under the pressure of particular circumstances (99). But the main conclusion is that in war, many roads may lead to success – but the reverse is true, too, not all means are neither guaranteeing success nor are legitimate.[6]

But the main conclusion is that in war, many roads may lead to success – but the reverse is true, too, not all means are neither guaranteeing success nor are legitimate.

Why is that so? Although Clausewitz finishes Chapter 2 of Book I with the notion that the ‘wish to annihilate the enemy’s forces is the first-born son of war’ (99), he emphasises that at a later stage and by degrees’ we shall see what other kinds of strategies can achieve in war’ (99). Nevertheless, he gives us two clues in this chapter. First, that war is not an independent whole but – an extension of the political sphere: that war has its own grammar but not its own logic.[7] Second, in my interpretation of Clausewitz, the difference between attack and defence represents a distinction between self-preservation and gaining advantages in warfare. Already in Chapter Two, he articulates the ‘distinction that dominates the whole of war: the difference between attack and defence. We shall not pursue the matter now, but let us just say this: that from the negative purpose [comes?] all the advantages, all the more effective forms, of fighting, and that in it is expressed the dynamic relationship between the magnitude and the likelihood of success’ (94).

My thesis is that Clausewitz is trying to combine the Aristotelian difference between poieses and praxis in his writings – an instrumental view of war for political purposes with the performance of the conduct of war, not just with the execution of the political will. Whereas for the early Clausewitz, the ‘purpose’ is a moment within the war, he later opposes this position, emphasising that this purpose is located outside of the actual warfare. With this differentiation of purposes in war and the purpose of war, Clausewitz covers a fundamental difference between various forms of action, which was initially developed by Aristotle and remains even today. The practical philosophy of Aristotle is based on the basic distinction of techne, as based on poiesis and phronesis, and praxis, based on performance and practical knowledge. Techne is technical, instrumental knowledge.

In contrast, phronesis or praxis of action can be characterised as performance in warfare. If we compare different purposes for going to war with each other, we are close to what Max Weber called the “value rationality” of purposes. Although Max Weber sometimes seems to overemphasise the difference between the rationality of purposes and military aims, his differentiation is useful to shed light on Clausewitz’s theory. Value rationality is primarily about the relationship of different purposes to one another, which can be classified into a hierarchy of purposes. The subordination of warfare to the shaping of international order, as Clausewitz puts it, is ‘value-rational’ as defined by Max Weber. By contrast, “action rationality” is a principle of action exclusively oriented to achieving a particular military aim through the most effective means and rational consideration of possible consequences and side effects.

Clausewitz initially makes a two-fold distinction between the purpose-aims-means relationship: first, as a value rationality, in which we find a hierarchical relationship starting from the purpose at the top, with aims and means subordinated respectively; second, as a process rationality, in which the military aim as the object of practical action is the output of the purpose-aim-means relationship.

He made this distinction at times only implicitly based on the different connotations of the concept of purpose. In part, Clausewitz differentiates between the purpose of war and the purpose in war. He used the same terms throughout, providing various contents from which this distinction could be deduced. Henceforth we need to have a further look at his use of terms and concepts.

Beginning with his earliest writings, Clausewitz asserted that war has a purpose. In his Strategie (Strategy), written in 1804, he wrote that the ‘purpose of the war’ can be: ‘Either to destroy the enemy completely, to remove their sovereignty, or to prescribe the conditions for peace.’ The destruction of the enemy forces is the ‘more present purpose’ of war. If the purpose of war, however, is the destruction of the enemy forces, is it a purpose that is realised within warfare?[8] The problem is that the destruction of the enemy moves from being a means to an aim in and of itself. In contrast to such an understanding of the purpose-aims-means rationality, for Clausewitz, the military aim within the war is an intermediary dimension between purpose and means. In his later writings, Clausewitz replaces the term’ purpose in war’ through the terms’ aims’ and ‘goals in warfare’ [(he uses the same German term Ziel for both aim and goal).

The late Clausewitz emphasises that the purpose of war lies outside the boundaries of the art of warfare. He argues that one must always consider peace as the achievement of the purpose and the end of the business of war. (215) ‘Even more generally, the consideration of the use of force, which was necessary for warfare, affects the resolution for peace. As the war is not an act of blind passion but is required for the political purpose to prevail, this value must determine the size of our own sacrifices. Once the amount of force and thus the extent of the applied force is being so large that the value of the political purpose was no longer held in balance, the violence must be abandoned, and peace be the result.’ (217)

Additionally, one has to take into account the counter-actions of the opponent. Clausewitz emphasises this difference in his chapter about the theory of war, Book Two: ‘The essential difference is that war is not an exercise of the will directed at inanimate matter, as in the case with the mechanical arts, or at matter which is animate but yielding, as in the case with the human mind and emotions in the fine art. In war, the will is directed at an animate object that reacts’. (149). Hence, Clausewitz’s final achievement is not a strategy that could be applied to all kinds of war but a reflection on the art of warfare, the performance of warfare within a political purpose.

If, as it seems to Clausewitz, the purpose of war lies outside of warfare and war is determined only as means for this purpose, then a technical, instrumental understanding of the war is thereby intended. But this is not the whole of Clausewitz. He also emphasises praxis, performance and practical knowledge. If the purpose lies within warfare, this does not contain a complete identity of the goal of martial action with its execution. In this case too, the purpose is not war for war’s sake. My conclusion is that Clausewitz is really trying to combine the Aristotelian difference between poieses and praxis in his writings – an instrumental view of war for political purposes with the performance of the conduct of war, not just with the execution of the political will.

Further dimensions of the concept of Purpose in Clausewitz

According to Herfried Münkler, Clausewitz makes a distinction between an existential and instrumental view of war. If purpose exists at the top of a hierarchy in the purpose-aims-means relationship, there is an assumption that war is instrumental, in the sense that there is a choice between different purposes, thus identifying the purpose in terms of Max Weber’s value rationality. However, if war is “existential”, in that the only purpose is the survival of the state, the hierarchy of the relationship is reversed, as the means by which the enemy is defeated gains primacy, which accords with a process of rationality. Clausewitz summarised the difference between both concepts of purpose: ‘Where there is a choice of purpose, one may consider and note the means, and where only one purpose may be, the available means are the right ones.’[9]

A pure process of rationality can lead to the fact that the military aim and means of warfare become the purpose in themselves. It is for characterising war in this manner, as an instrument facing inwards on itself, rather than outwards to a wider political purpose, that the early Clausewitz can be criticised. He adopted the Napoleonic model from Jena, trying to seize its successes systematically and, without considering the social background of France, to generalise it as an abstraction. In his critique of Clausewitz, Keegan wrote that the military develops war cultures, which correspond with their social environment. If, however, war is seen as purely instrumental and the connection to this environment is cut, then the danger of blurring the military boundaries threatens potentially endless violence. In this view, the roots of Clausewitz’s image of war refer back to the origins of the modern age, which was characterised by the full possession of civil rights, the general right to vote and compulsory military service, all of which completed the portrait of the citizen soldier and the ‘battle scenes’ of the people’s army.

The question for today is whether the revolution in military affairs as well as fourth and fifth-generation warfare (5th generation warfare is partisan warfare applied by states or state-like entities like Hamas) are tempting to a primacy of the means and aims over meaningful purposes, a primacy of tactics over strategy and the ‘art of war’, which is in Clausewitz’s view even surpassing strategy.

The French model was, in fact, adapted for the Prussian circumstances: a revolutionary people’s army in the service of the raison d’ état – but without ‘republic’ (meaning a democratically constituted system of government). In this form, Clausewitz’s theory was proved and began to be used later for multiple purposes. It started its triumphant advance through the general staff throughout the war ministries of the world. In Keegan’s view, the result of this process was the general armament of Europe in the 19th century and its excessive increase in the 20th century.[10] Keegan left unmentioned that Clausewitz’s theory of war had yet to be bisected to fulfil this function, especially by the German general staff in the First World War. Nevertheless, his criticism revealed a fundamental problem of modern war: the separation of potential options for warfare from socially meaningful purposes. In World War I, tactics replaced strategy.

Although the understanding of the strategy of the early Clausewitz was, in fact, one of an aim or goal independent from the political realm within warfare, the definition of purpose of the later Clausewitz is based on the political purpose outside of warfare. There are still passages in the final version of On War in which Clausewitz does not differentiate clearly between purpose and aims. The question for today is whether the revolution in military affairs as well as fourth and fifth-generation warfare (5th generation warfare is partisan warfare applied by states or state-like entities like Hamas) are tempting to a primacy of the means and aims over meaningful purposes, a primacy of tactics over strategy and the ‘art of war’, which is in Clausewitz’s view even surpassing strategy.

Notes:

[1] The relevant discussions may be found in the following books: Echevarria, A. 2007. Clausewitz and Contemporary War. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Gray, C. 1999. Modern Strategy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Herberg-Rothe, A. 2007. Clausewitz’s Puzzle: The Political Theory of War. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Keegan, J. 1994. A History of Warfare. London and New York: Vintage; Simpson, E. 2012. War from the Ground Up: Twenty-First Century Combat as Politics. London: Hurst; Strachan, H. 2007. Clausewitz’s OnWar. Atlantic Monthly Press, New York; von Ghyczy, T., Bassford, C. and von Oetinger, B. Clausewitz on strategy. Inspiration and insight from a master strategist. Hoboken: Wiley; Heuser, B., 2010, The Evolution of Strategy: Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Heuser, Beatrice 2010, The Strategy Makers: Thoughts on War and Society from Machiavelli to Clausewitz. Praeger Security International:

[2] For details, see Herberg-Rothe, Andreas, Clausewitz’s puzzle. Oxford University Press: Oxford 2007. Clausewitz, Carl von; 1990. Schriften, Aufsätze, Studien, Briefe, vol. 2, ed. W. Hahlweg. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck&Ruprecht.; Clausewitz, Carl von, 1992. Historical and Political Writings, ed. P. Paret and D. Moran, 1992. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; Clausewitz, Carl von, Politische Schriften [Political Literature], ed. H. Rothfels. Munich: Drei Masken Verlag. 1922.

[3] The numbers in brackets are references to Clausewitz, Carl von, On War. Translated and edited by Peter Paret and Michael Howard. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1984. As translation is a highly tricky process, I have tried to make some translations of my own only in some cases, especially in trying to distinguish the German terms „Zweck“ and „Ziel“. These terms have been translated as purpose, object, objective, ends, and as aims, goals and sometimes even ways by Howard and Paret. My main intention in this article is to distinguish between purpose and aims. It might be that the great variety of the translations has contributed to the underestimation of the difference between the purpose of the war and the goal within the war. Although they are closely connected with each other, I follow Clausewitz’s assertion that the same purpose could be reached by pursuing different goals.

[4] With this notion, we can explain the difference between Clausewitz’s real concept of the trinity and trinitarian warfare, which is not directly a concept of Clausewitz, but an argument made by Harry Summers, Martin van Creveld and Mary Kaldor. In trinitarian warfare, the three tendencies of war are understood as a hierarchy, whereas Clausewitz describes his understanding of their relationship as a floating balance In my view, each war is differently composed of the three aspects of applying force, the struggle or fight of the armed forces and the fighting community the fighting forces belong to; based on this interpretation I define war as the violent struggle of communities; see Herberg-Rothe, Clausewitz’s puzzle.

[5] This reference seems to strengthen the difference made by Emile Simpson between the use of armed force within a military domain that seeks to establish military conditions for a political solution on one side and the use of armed force that directly seeks political as opposed to specifically military outcomes; Simpson, War from the ground up, p. 1.

[6] The confusion about the difference between Zweck (purpose) of and Ziel (aims) in warfare concerning Clausewitz might be additionally caused by his own insufficient differentiation in this chapter.

[7] For Clausewitz’s concept of Policy and politics, see Herberg-Rothe, Clausewitz’s puzzle, chapter 6.

[8] Clausewitz, Carl von, Strategie aus dem Jahre 1804 mit Zusätzen von 1808 und 1809 (Strategy from the Year 1804 with Additions from 1808 and 1809). In EB, Verstreute Kleine Schriften (Small Scattered Writings), pp. 3-61, here pp. 20-21.

[9] Clausewitz, Carl von, Historisch-politische Aufzeichnungen von 1809 (Historical-Political Records of 1809). In: Clausewitz, Carl von, Politische Schriften (Political Literature), p. 76.

[10] . Keegan, Kultur des Krieges (The Culture of War), in particular, p. 543; Naumann, Friedrich, An den Ufern des Oxos (On the banks of the Oxos). John Keegan corrects Carl von Clausewitz. In: Frankfurter Rundschau from 17.6.98, p. ZB 4.

Feature Photo Credit: Dennis Jarvis – War on the Rocks