With global crises such as the 2008 financial crisis and more recently the COVID-19 pandemic, monetary policy worldwide has increasingly ventured into uncharted territory. In the last 10 years alone, the world has seen 3 major crises that have affected financial markets extensively. Given the increasingly complex nature of economies and financial markets, central bankers have had to function under great uncertainty and shrinking policy space. Even as governments and policymakers worldwide leave no stone unturned in the fightback against crises, the traditional policy has often fallen short of its objectives. In light of growing limits of existing policy tools during a crisis, it has forced central banks to resort to unconventional measures such as negative interest rates (NIRP), quantitative easing, forward guidance and yield curve controls. Before the financial crisis of 2008, such unorthodox policies were relatively less commonplace. Today they are increasingly becoming key components of the monetary toolbox. However, much of these new policies is yet to be studied or tested in the real world. The long-term effect of such policies is still unclear. In this light, it becomes imperative to understand and analyse these unconventional policies to chart a course for monetary policy in the near to long term.

What is Unconventional Monetary Policy?

Under normal conditions, the most powerful weapon in a central banker’s toolkit is the policy interest rate. However, as global financial markets get more interconnected and complex, central bankers have to act under great uncertainty. As crises push traditional policy tools to their limits, central bankers have had to bank on more unconventional policies than ever before. As the governor of the Swedish central bank, Stefan Ingves puts it, “Monetary policy and the way we ‘do’ monetary policy has changed. All the time, we need to stand ready to develop new tools and make new kinds of analysis – If the world changes, we need to change with it”.

Figure 1: Policy Tools Comparison

Typically, interest rates and money supply are the two run-of-the-mill tools that central bankers resort to. Extreme versions of these policies, such as negative interest rates and quantitative easing, are termed unconventional monetary policies since they deviate from the traditional policy measures of a central bank. According to RBI’s Deepak Mohanty, “When central banks look beyond their traditional instrument of policy interest rate, the monetary policy takes an unconventional character”. Essentially, an Unconventional monetary policy is a set of measures taken by a central bank to bring an end to an exceptional economic situation. Central banks use these measures only in extraordinary situations when conventional monetary policy instruments cannot achieve the desired effect [1].

Quantitative Easing

Quantitative easing (QE) is a form of extreme and targeted control of the money supply in the economy. At its core, QE seeks to increase the money supply in the economy through the purchase of securities and bonds in the open market. When a central bank uses QE, it purchases large quantities of assets, such as government bonds, to lower borrowing costs, boost spending, support economic growth, and ultimately increase inflation.

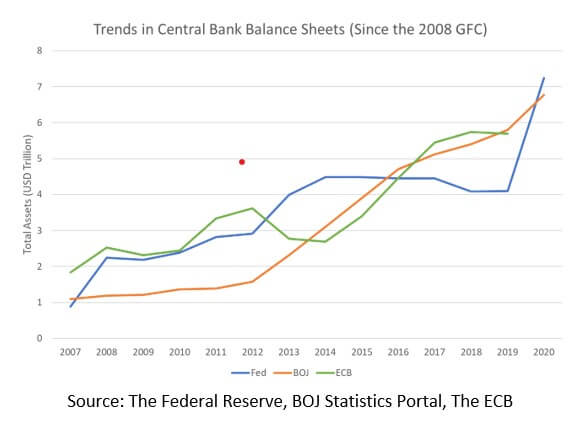

Before the 2008 financial crisis, only one major economy, Japan, had implemented a significant Quantitative Easing program in the 1990s. Today, however, almost all major economies have some sort of QE or an asset purchase program. According to a report by Fitch Ratings, global QE asset purchases are set to hit $6 trillion in 2020 alone, which is more than half the cumulative global QE total seen over 2009 to 2018 [2]. As seen in the figure below, the balance sheets of major central banks have been expanding significantly since the financial crisis.

Figure 2

Quantitative Easing has been the cornerstone of the Fed’s crisis response since 2008. In the three rounds of QE post the 2008 crisis, the Fed balance sheets increased from $870 billion in August 2007 to $4.5 trillion in early 2015. Earlier this year, the Fed purchased a record $1.4 trillion worth of US treasuries in just six weeks in response to the COVID-19 crisis, speaking volumes of the role played by the unconventional policy during a period of crisis. Also, it’s not just the advanced economies that are resorting to extensive QE programs. Nearly 13 emerging market economies, including India, announced some form of a QE program following the crisis. In India, the RBI injected durable liquidity of ₹1.1 lakh crore through the purchase of securities under open market operations (OMOs) [3].

Zero or Negative Interest Rates

Quantitative easing was just the beginning of the long list of tricks central bankers pulled out of their sleeves. Closely accompanying QE policies were accommodative monetary regimes of ultra-low interest rates. In 2020 alone, interest rates have been slashed across the globe on 37 separate occasions [4]. Interest rates have been falling across the globe even before the crisis, and the current pandemic has only sped up this fall.

While many economies have reached the theoretical zero lower-bound of rates, some have even dared to venture below the surface into negative territory. As of today, 5 economies in the world follow a Negative Interest Rate Policy. While the very concept of negative rates may seem baffling, it’s even more shocking to note that over $15 trillion worth of bonds is traded at negative yields globally [5]. This means that over 30% of the world’s investment-grade securities are traded in a manner such that lenders pay borrowers to use their funds. Central banks envisage that negative policy rates would induce increased spending and stimulate the economy in two ways – first, by forcing banks to hold lesser deposits with the central bank and channelling these funds into increased lending to households and businesses. Second, a cut in the policy rate would also lead to lower rates in the overall lending market, thus encouraging borrowing and spending.

Forward Guidance

Forward guidance refers to official communication from a central bank on the future course of monetary policy in the economy for a specific period. It is more of a monetary policy stance than a monetary policy tool. The key idea here is to keep markets informed and eliminate any form of uncertainty, which becomes especially imperative during times of crisis.

Figure 3

Gone are the days when central bank rate cuts and other announcements of secrets that were sprung upon the markets when they least expect it. With forward guidance, central banks provide communication well in advance about the likely future course of monetary policy in the economy, and this boosts the confidence of investors, consumers and companies. The US’s Fed was one of the major central banks to adopt this policy during the COVID crisis – providing clear forward guidance in June showing that it will probably keep rates low until at least 2022. The policy has been the cornerstone of the Eurozone’s crisis response since the sovereign debt crisis. In July 2012, at the height of the crisis, ECB President Mario Draghi adopted a form of Forward Guidance, stating that the ECB will do “whatever it takes” to save the euro. It is believed that these three words single-handedly turned around the eurozone crisis.

Are Unconventional Policies Here to Stay?

Apart from QE, NIRP and FG, there are several other unconventional policies in practice world over – Australia is experimenting with yield curve controls, the Fed is attempting to influence markets with forward guidance while Japan is considering printing helicopter money. There are so many extreme measures being adopted across the globe that policy commentators are now referring to these nations as swimming in an alphabet soup of unconventional policies (QE, NIRP, ZIRP, U-FX, NDR etc.). Post the 2008 crisis, when such policies were first being debated upon and economies were just dipping their toes in the ocean of unconventional policy, many warned of dire consequences such as hyperinflation and collapsing currencies. Luckily for central bankers, none of these predicaments came true. Most advanced economies are still struggling to combat deflation and extremely low levels of inflation despite adopting several unconventional policies. In this scenario, fears of hyperinflation seem to be unwarranted. While there have been studies documenting the potentially harmful effects of unconventional policies, economies still seem to stick with these policies. On one hand, central bankers have no better alternative tools, and second, the positive effects seem to fairly outweigh the negative externalities.

Thus, unconventional policy tools are going to be around for the near future. As economies and global markets grow more complex, so will the policies and policy tools regulating them. Similar to how drastically monetary policy has changed within just 10 years after the financial crisis, it will keep evolving and adapting with time by developing new tools and analyses. Monetary toolbox a decade or two later will look radically different from what it is now. The important question then becomes not whether unconventional policies are here to stay, but how nations can make the most effective use of them.

The new monetary tools, including QE and forward guidance, should become permanent parts of the monetary policy toolbox – Ben Bernanke, Ex-Fed Chair

Need for Monetary Policy and Fiscal Policy to Work in Tandem

While central bankers have no stone unturned in the fightback against crises, the success of unconventional policies has been fairly moderate. In Japan, for example, the NIRP has failed to stimulate spending and investment in the economy. Rather, negative rates have only forced a massive outflow of funds from the country in favour of foreign assets. In the Eurozone as well, the policy has achieved no significant impact, with banks continuing to pay billions of euros as negative fees to the ECB. While QE has fared slightly better than the rest as a policy tool, the experiences of various economies with it have been mixed.

The experiences of several economies have shown that while unconventional policies may work better than conventional ones during a crisis, there are limits to their performance as well. One of the key failures of unconventional policies (and conventional policies) has been the inability to stimulate healthy inflation in recessionary economies. Policies such as QE and NIRP, despite increasing the monetary base of economies, have failed to spur spending and investments. As we have seen in Japan, a standalone monetary policy, no matter how accommodative, is insufficient to pull economies out of downturns. In this light, it is imperative that monetary policy, conventional or unconventional, be accompanied by temporary fiscal stimulus during recessions. Public investment in infrastructure could give economies a much-needed boost in the absence of a private appetite for investments. Infrastructure is an enormous economic multiplier, and governments would do well to work in tandem with monetary regimes to provide the initial spur in economic activity. Several studies have shown that public investment during crises can generate employment and increase output. Originally theorised by British economist J.M. Keynes, the ‘Keynesian Multiplier’ of government spending could be the magic potion that makes unconventional policies go from good to great.

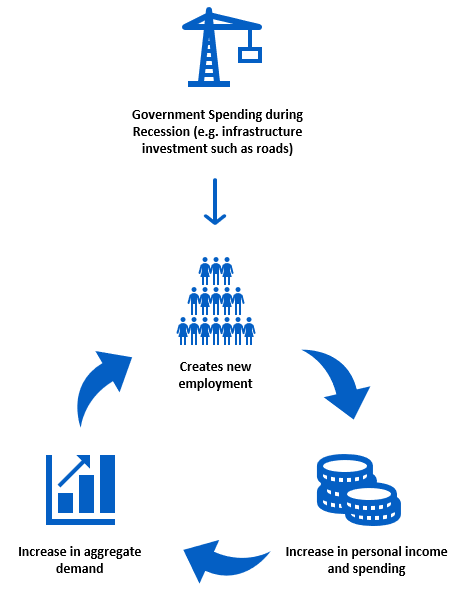

How does the Keynesian Multiplier Work?

During times of recession or economic downturn, government spending puts into action the Keynesian Multiplier. According to the Keynesian Multiplier, theorised by prominent economists such as Keynes, Kahn and Hicks, short term government spending boosts the economy by more than what is spent. Keynes was of the view that during a recession with a high level of unemployment, Governments should raise public spending to sustain effective demand and profits.

Figure 4

As seen from the figure above, an increase in government spending on large projects such as road building will lead to the creation of alternative employment. The increase in personal incomes and consequently aggregate demand in the economy will further stimulate economic activity and will create more employment than what was originally created by government spending. In effect, every unit of money spent by the government during a downturn increases GDP by a greater proportion than what was spent.

Conclusion

While unconventional policies are here to stay, they are a step in the dark. Economies are still experimenting and attempting to figure out the most effective use of these policies. Considering the fairly moderate performance of standalone unconventional policies, there is an established need for complementary fiscal policy to accompany monetary policy. An increase in infrastructure investment coupled with an accommodative monetary regime could help stimulate stagnant demand during a crisis. In developing economies, it can also help address structural bottlenecks subduing growth. These investments from the government, however, must be productive and efficient. Otherwise, they just end up adding on to already high levels of debt, especially during periods of crisis when governments have to borrow extensively for emergency requirements. It is also imperative that this investment is temporary and not permanent. Long-term government debt is unsustainable and can crowd out much-needed private investment.

References

[1] Central Charts. (2019). Definition of Unconventional Monetary Policy. Retrieved from [2] Fitch Ratings. (2020). Global QE Asset Purchases to Reach USD6 Trillion in 2020. Retrieved from

https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/global-qe-asset-purchases-to-reach-usd6-trillion-in-2020-24-04-2020

[3] Reserve Bank of India. (2020). Policy Environment. Retrieved fromhttps://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=20269

[4] Desjardins, J. (2020, March 17). The Downward Spiral in Interest Rates. Visual Capitalist. [5] Mullen, C. (2020, November 6). World’s Negative-Yield Debt Pile Has Just Hit a New Record. Bloomberg Quint.

Image Credit: The Conversation